Time is short for most visitors to Berlin. This means they understandably focus their visit on the historic city, the side of town that became east Berlin – the former Soviet sector.

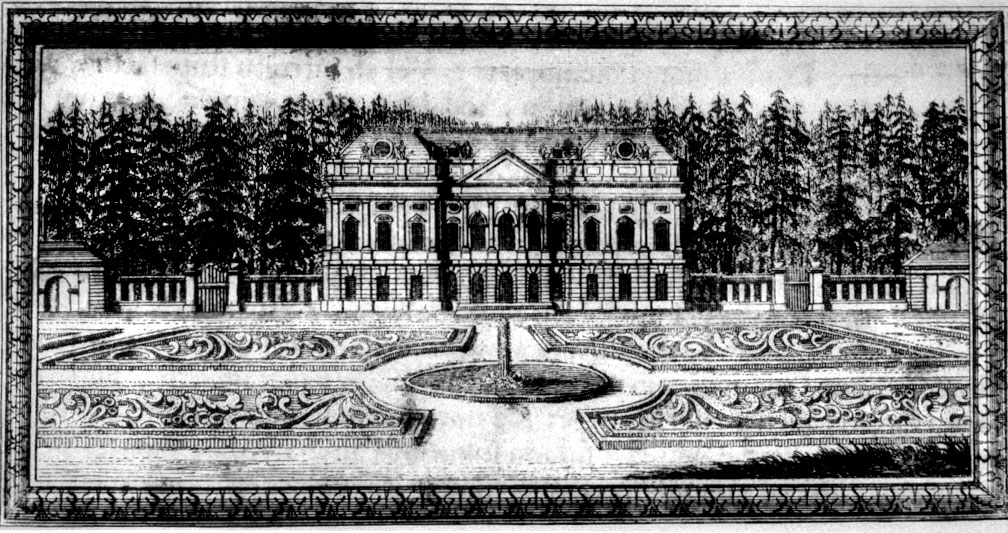

This is a shame, as they miss out on something rare in west Berlin – the spectacular Charlottenburg Palace.

Why rare? Because the ravages of war-time bombing, and equally importantly, the politically driven demolitions after the war removed Berlin’s main city palace and other historic buildings.

The Charlottenburg Palace was burned out by 1945, but restored to its (almost) former glory in the 1950s, and is the largest Prussian palace still standing in Berlin today.

Opening originally in 1699, it can be seen as a symbol of Berlin’s early 18thcentury ‘coming of age’ as the capital of Prussia and a ‘European city’. This step would set Berlin on a path, rising to the status of ‘world city’ by the end of the 1900s, just then to fall so far in the 20th century.

Today, the district of Charlottenburg is the heart of western Berlin once more. It’s a young district of city, built first only in the mid 19th century as a bourgeois leafy villa suburb. At its heart is still the famous Kurfürstendamm shopping mile and Zoological Garden.

At the time of the original conception of the palace, Charlottenburg itself was still countryside, basically just a village called Lietzow, by a small lake. But here was available space, close to the city, and that caught the eye of the man who would be king.

The palace was built by the Hohenzollern ruler of Berlin and Brandenburg, then the Elector Frederik III. Then he became King Frederik I.

His family’s centuries long ambition for parity with the older, grander royal houses of Europe drove him to declare himself King in Prussia in 1701. Prussia proper was an enclave in what’s now western Lithuania. This was territory Berlin controlled, but was importantly beyond the influence of Frederik’s powerful allies, and a place they couldn’t deny him being king ‘in’.

This ambition can be seen in the style of the palace itself. King Frederik I had it built for his second wife – Sophie Charlotte of Hannover. The surrounding district is named after her. She died 5 years after she moved into what was essentially her new, summer residence.

Designed by architect Nering and expanded by Eosander, the Charlottenburg palace was first inspired by the famous Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, and its gardens by Versailles.

The gardens themselves hide some jewels not be missed and are worth a wander. There is the Belvedere (lit. ‘nice view’) a tea house designed by the builder of the Brandenburg Gate – K. Langhans. There is the beautiful neo classical tomb – the ‘Mausoleum’ – containing the sarcophagi of King Fredrik Wilhelm III and his wife, Queen Luise, a Berlin legend who stood up for Berlin’s pride after it had been defeated by Napoleon. Her son was King Frederik Wilhelm IV, his heart is buried at her feet. Here too lie the first German Emperor Wilhelm I and Mrs Emperor.

Perhaps the most famous thing associated with the Charlottenburg Palace is the legendary Amber Room.

Conceived and built at the same time as the Palace itself, it consisted of over 400 tons of Baltic Amber, carved, bejewelled and beset with paintings, to be seen best in candlelight. This spectacular creation was the wall panelling to end all wall panelling.

Originally, it was to adorn the Charlottenburg Palace, but it was eventually built into Berlin’s main Town Palace, recently reconstructed on today’s Museum island in the city centre. Having been gifted generously to Tsar Peter the Great in 1716, it disappeared from St Petersburg during WWII.

The search for its whereabouts are still ongoing, and the stuff of Indiana Jones (check this out for an overview)

Coming to Berlin? – let’s explore the Charlottenburg Palace, it can be combined in a Baltic Cruise Shore excursion to Berlin – we can make our starting point (check out my Berlin tours).

Anti-Semitism has a very long pedigree. Often, when one reads about gravestones being damaged in this context, it is Jewish headstones that have been targeted. This story is different.

The relationship with its Jewish community will forever be part of Berlin’s story. It is on the whole, a very ugly story, everywhere.

Today, Berlin’s monuments, exhibitions and study centres to this history are rather admirable. Here and there around the city are also reminders, tiny pin pricks of light in that deep, 12-year darkness as Hitler’s capital, that hint too at ‘what if?’ or ‘if only.’

The removal of reminders of uncomfortable history is an ongoing and contentious debate globally. Retrospective re-evaluations of the past often seem ignorant, lacking and lazy. The genuine relic, however uncomfortable the story it represents, cements authenticity and becomes a core around which discussion, fact and understanding can be built today.

Berlin has tussled with this debate, perhaps more intensely than other cities.

A Berlin metro station name came up for review recently. The station’s name – Möhrenstrs – or ‘Moor Street’ was the issue. No longer acceptable said some in today’s Berlin. This story has drifted from the front pages now, after a few new name proposals foundered. But if you missed the story here it is.

Berlin street names have been changed more often than most cities. Imperial period names morphed into Nazi. Then after World War II, both east and west Berlin relaunched with their own labels, and now there are some new modern ones too. It is a terrible irony that one of the longest lasting street names is Jüdenstrs, Jews Street, now both a testament and an accusation, and still signposted in the Berlin medieval period city centre area today.

One street name controversy that has rumbled for years, and seems pretty simple to resolve but hasn’t been, is Heinrich von Treitschke Straße. My daughter’s school was on this road.

He was an individual with unpleasant ideas, who lived in a time when many already knew better. Treitschke was quoted by the Nazi regime – if fact his quote appeared as a slogan on a newspaper front page every week, then available in all good Nazi newsagents near you – from 1923 until February 1945.

The name of the repulsive paper was the ‘Der Stürmer’, the content a slop of violent anti-Semitism and brutal adolescent pornography . The phrase was at the bottom of the front page was: ‘The Jews are our misfortune’

Violent antisemitism and brutal, emotionally adolescent violent pornographic fantasy sums up the Nietzschean ‘mass man’ that characterised many a the Nazi follower cum perpetrator. Godless, lawless, boorish, basic, childish, savage and completely unable to see their own degradation.

This should be born in mind when pondering today Hitler’s seemingly inexplicable appeal. The cheering masses in the beer halls, Hitler’s audience, where these folks.

Even the more erudite audience members experienced something peculiar. The German population, traumatised by the end of WWI and the myriad disasters of the 1920s, sought succour increasingly desperately, and in increasingly fringe places.

That is why Hitler was so effective. Millions of Germans abandoned the rational, the fair, and the logical and responded with a leap of faith to the emotional and self-interested, wallowing in dreams of revenge and the ecstatic vision of Hitler’s ‘quick fix’ redemption offer.

All you had to do was believe. Hitler’s speeches weren’t interesting, they were moving.

In this type of atmosphere emotive slogans and images wield power.

Hence the effectiveness of the phrase ‘the Jews are our misfortune’

Treitschke was a product of the main streams of German consciousness of the mid 1800s. As a member of parliament in the Reichstag he represented German nationalist parties and views. He was a contributor to a world into which Hitler was born. Treitschke is also quoted thus: ‘Brave peoples expand, inferior peoples perish’. This could easily have come from the Führer himself.

Where did these come from? Post French Revolution democratic fervour had spilled over into Germany by the mid 19thcentury. Industrialisation had produced a new, educated middle class that wanted representation. The workers and farmers too felt ripped off. The ruling aristocratic castes were afraid.

This catalysed debates about a new German democracy, nationalism, and imperial ambitions, often underpinned by crude notions of social Darwinism. Unfortunately, at this time, German Jewish emancipation was up for debate (again). There was also the sudden realisation that modern industrial economies and stock markets could fail. It was a new world in which some German Jews, brave and innovative, excelled. It’s failures demanded scapegoats.

These sentiments, combined eventually with broad feelings of national self-pity, jealousy (v. Treitschke was vocally anti British empire) and stupidity, contributed to the slide into World War I.

v. Treitschke died in 1896, not seeing that that he had in part inspired (the question of whether he would have been moved by Hitler’s speeches is moot as he was deaf).

He was buried in the St Matthews cemetery in Berlin, a resting place of more illustrious dead, perhaps these men are the most significant. Treitschke was a well-known figure, and his grave is substantial, made up of a costly, black-green granite head stone and flat grave-cover slab.

But today, if you look closely at this grave, you see now see something peculiar.

On the flat gravestone, under his name and dates, there are two carved scrolls. These remains untouched, and might have originally flanked a central symbol, perhaps an Iron Cross.

But at some point, probably in the 1980s, this part of the slab was ground down by persons unknown, mechanically, leaving the central section smooth and shiny. And then, with power tools, a neat star of David has been cut into the space. It’s deep and carefully executed. Only the left-hand angles seem a bit ‘off’. This hints that this person was perhaps not a professional, was determined (it’s cut into granite) and perhaps was working hurriedly as one would expect if one had lugged power tools, and a power source into a cemetery to amend a grave.

Who did this is remains a mystery. Why is pretty obvious. It looks like the ‘amendment’ will stay there as long as the grave. A strange victory.

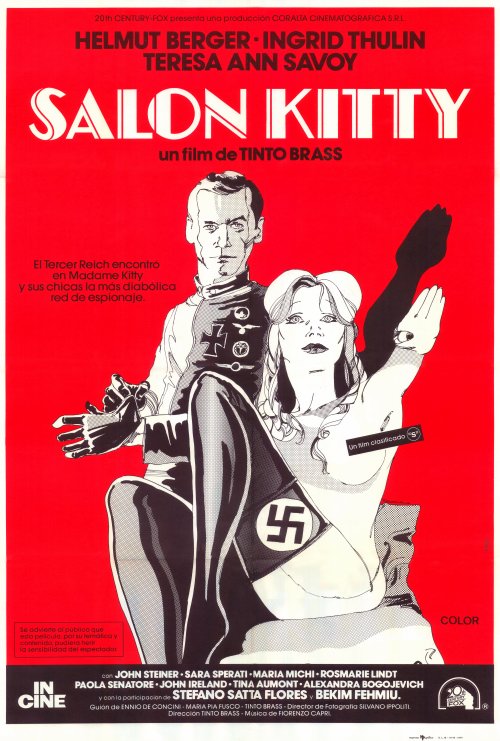

Salon Kitty

In 1938, Nazi Holocaust manager Heydrich opened Salon Kitty, a brothel in Berlin west, bugged to spy on its high powered patrons. Now, half empty, I recently gained access - see what it's like inside Salon Kitty today.

The Man who enabled Hitler.

Gürtner enabled Hitler, at several crucial junctures on his road to power, to survive. Without him, Hitler would not have become Hitler. No Hitler No Holocaust. No Gürtner No Hitler.

Bullets and connections of Operation Barbarossa.

On this day in 1941 Hitler's Operation Barbarossa was launched against the Soviet Union. This would become the beginning of the end of WWII in Europe, but for me there are other connections...

Escape to Checkpoint Charlie.

Many visitors to Berlin claim to be disappointed when visiting Checkpoint Charlie - without which no Berlin visit is complete. Read this to make it come alive.

Forgotten corners of Berlin’s Tiergarten park.

During Lockdown many Berliners rediscovered the city parks. The most famous is the Tiergarten. There are still some forgotten corners worth discovering.

Killing Hitler – a persistent historical error at the Wolf’s Lair.

Some brave people attempted to stop Hitler. But there is an error in the story of the attempt that came closest, in 1944, at the Wolf's Lair.

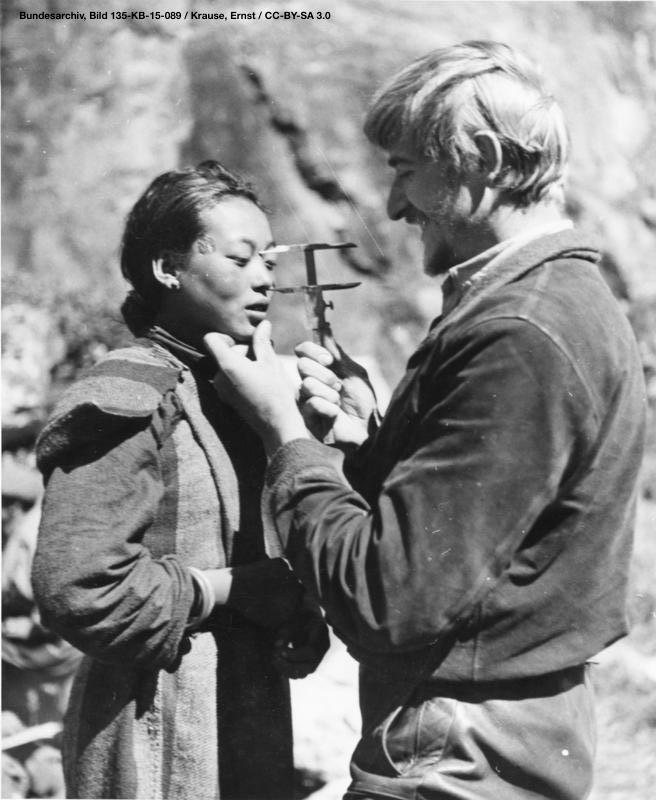

Namibian Genocide and Himmler’s ‘Ahnenerbe’.

Today Germany has acknowledged responsibility for the genocide of the Herero in Namibia in 1904. There is a dark connection between this and Heinrich Himmler, laughable if it wasn't so disgusting.

Art & Reality – Berlin Battlefield Damage

This is a bronze sculpture showing some Berlin battle field damage from 1945. The real shell hole it depicts exists, but there's a slight problem...

Visit Schloss Charlottenburg Palace

Schloss Charlottenburg is the largest Prussian palace left in Berlin, sadly missed by many & is well worth a visit! One fascinating story - it was the original home for the legendary Amber Room that disappeared during WWII.....

A strange victory – the embellishment of Heinrich von Treitschke’s Berlin grave .

The strange story of 19th century anti-semite Heinrich von Treitschke, used as a powerful tool by the Nazis, and the odd story of what happened to his grave.

The women who blew up Berlin

After WWII, the famed ‘Rubble Women’ cleared broken Berlin by hand, creating the ‘rubble mountains’ on both sides of the city. But one women was a different type of rubble women. She didn’t remove it. She created it. Her name was Hertha Bahr. And she blew up bits of Berlin.

Get in touch with me

info@jacksonsberlintours.com

Do you have any questions?

Jewish Berlin Capital of Brilliance and Tragedy

About as long as there’s been a place in recorded history called Berlin there’s been a Jewish community living here. We start in the oldest section of the city, where the 14th Century Jews lived in the ‘Judenhof’ and at adjacent Alexanderplatz.

Book your tour now: