In 1938, the head of the Nazi security agency and man who would later manage the Holocaust – Reinhardt Heydrich- opened a high-class brothel on a leafy, residential Berlin street.

Staffed by 20 specially selected and trained prostitutes, it catered for the elite of the Nazi party and their foreign visitors. Patrons including propaganda minister Goebbels, Mussolini’s son in law Count Ciano, the head of Hitler’s today guard regiment and Himmler’s right hand man Heydrich himself.

Named after madam Kitty Schmidt, ‘Salon Kitty’ was not just a palace of pleasure for top Axis members, but Heydrich had the venue bugged to spy on his allies who might offer information at such an indiscreet venue.

Bombed out by the end of the war, the house returned to civilian use. Today half of Salon Kitty lies empty waiting for new tenants. Recently, I gained access to the very rooms of Salon Kitty today. To see the pictures and hear the story click here .

Attempts to answer the great, universal questions can be provided by two disciplines – science and religion. The former produces a list of details on ‘how’, the latter offers theoretical options on ‘why’, in which one can place one’s faith. Or not.

The same can be said about historians and the questions of the Third Reich. The ‘why’ is still both debated and often obscene. But there is a significant and forgotten ‘how’. And its name is Franz Gürtner.

Gürtner enabled Hitler, at several crucial junctures on his road to power, to survive. Without him, Hitler would not have become Hitler.

Hindsight history is full of ‘if only’. If only more back-bone had been shown against Nazi Germany’s risky aggression during the reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936. If only Stauffenberg’s bomb had killed Hitler in 1944 and so on. Surrounding all these hypotheticals are explanations, provisions of context and mitigating circumstances, even caveats of what futures these events might have produced had the ‘right’ thing been done at the time. All this adds to the merry-go-round of historical debate.

These examples look back and identify alternative courses of action that would have produced a better world. But at the time, there was already a mechanism that could have kept the name Hitler to just a footnote of history. It was the state institution that collates rules to regulate society, behaviour and punishment for the good of the whole: The Law. If it’s clear statutes had been followed in the 1920s, Hitler would have sunk with little trace.

But in those turbulent years of Hitler’s early political career, the law wasn’t obeyed. By 1933 it was too late. Soon after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor, Germany became a county where the fair rule of law ceased to apply. Swathes of citizens whose choice of political views, or simply their ethnic heritage, clashed with the Nazis views, now fell outside its protection.

The law was now subject to Hitler’s whim. In August 1940, the German Minister for Justice himself said, in response to a local judge objecting to what was simply illegal, government sanctioned mass murder: “If you cannot recognise the will of the Führer as a source of law, then you cannot remain a judge”. This minister’s name was Franz Gürtner, the mass murder the Nazi Euthanasia program that began in September of 1939.

Gürtner was Bavarian civil servant who initially worked in the state’s Justice Ministry. In his early 30s he served with distinction in the German army during WWI. Upon his demobilization, he was absorbed back into the Justice Ministry in Munich. The political aftermath of WWII here was chaotic. His nationalist sympathies saw him become a member of the German National Peoples Party, the DNVP. Revolution in Bavaria in 1919 produced the ‘Republic of the councils’, a short lived left-wing government. This was violently over thrown by an independent army of ‘freikorps’ forces. One of the common soldiers supporting the left-wing regime was in reality a stool pigeon, who betrayed his comrades in the aftermath of the right-wing take over. This soldiers name was Adolf Hitler.

For many like Gürtner and Hitler, WWI didn’t end in 1918/19. The war continued against the young democracy – the Weimar Republic. Brutalised ex-soldiers with nothing to lose perpetrated murder after murder in their struggle against what they saw as the betrayers of Germany. The 1922 drive-by shooting of Foreign Minister Rathenow in a wealthy Berlin suburb perhaps the most well-known of these assassinations. These crimes could not go unpunished. So, in Bavaria, an official was commissioned to investigate the murders, and in a secret protocol told not to solve them. The murderers would go unpunished. This officials name was Franz Gürtner.

Hitler’s role during this chaos was as a local political celebrity, agitator and provocateur of violence. Many times, after Hitler spoke, people died. Often he had been called to account by the Bavarian state wanting to censure him for his law breaking. Hitler would grab second chances by swearing he would stop illegal activities. The dilemma was that Hitler’s party represented views that were broadly shared by the anti-democratic ‘secret army’ of demobilized soldiers now serving in positions of power in Bavaria. It was these same men that had deliberately failed to mete out justice for the political murders they silently supported.

In 1924 they had another important court case to judge in Munich, an event that had left 16 men dead.

In 1923, the traumas of the lost war and inflation was finally subsiding. Foreign financial investment was to produce several ‘good’ years. Hitler, desperate to grab a chance to increase the fear and chaos on which he thrived politically, launched his ill-fated coup d’étatin Munich in November 1923.

It failed, and as the shooting started Hitler was the first to run away. He was arrested. During the trial the prosecution had trouble looking the treasonous defendants in the eye. This is because they knew each other, worked together and supported each other. The result was a lenient sentence for Hitler. Five years. And no deportation from Germany – a fate that would have befallen any other foreigner who had behaved as Hitler had done in the years before.

The name of the man who allowed Hitler to take over the trial with his defence, and whose gavel sealed his light sentence, was Franz Gürtner.

Nine months later, Hitler was released. Whilst in prison he had become forgotten by most of his colleagues, and his movement had disintegrated. The Nazi party had been outlawed and Hitler had been banned from public speaking. But by 1926 both these bans too had been lifted. Working behind the scenes to lift both of these prohibitions, successfully, was Bavarian Justice Minister, Franz Gürtner.

By 1932 both Gürtner’s and Hitler’s stars had risen. Gürtner was now national Minister for Justice, a positon he retained when Hitler became chancellor in January 1933. He was instrumental in creating the sweeping laws for dictatorial power after the Reichstag fire, and in 1935 the infamous racial/legal code known as the Nuremberg laws. Though he did eventually attempt to mitigate against the most embarrassing and obvious Nazi perversions of law, he served in his position until his death in 1941.

Gürtner and many others believed that Germany could alleviate the shame of defeat in 1918 and reassert its destiny as a world power by ridding itself of ‘weak’ democracy and replacing it with a strong dictatorship to correct the national course. To achieve this quickly they were prepared that the law, something they had studied and represented, might have to be bent in the short term.

Alas, it was this deal that Gürtner and millions of other Germans were prepared to accept to assuage their adolescent rage at the realities resulting from national hubris and stupidity before and after WWI. Even though Gürtner died before witnessing the full harvest of what he had helped sow, he must have realized that the bargain had turned sour. WWII itself was part of this deal. It was during this phase that Gürtner’s actions led to his country and huge swathes of the world being turned into a charred hell-scape, where millions died.

Gürtner and others were familiar, I’m sure, with the work of enlightenment philosopher John Locke. He wrote: ‘Wherever law ends, Tyranny begins’. Men like Gürtners willingness, particularly those that represented the law and the Justice Ministry of the German government, to ‘work towards the Fuhrer’ after 1933, bear a special responsibility for the horrors that they went out of their way to enable.

No Hitler – no Holocaust.

No Gürtner – No Hitler.

#OTD in 1941 the German Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union. With around 3.3 million troops, and 6.6 thousand tanks and aircraft, and supported by over a million horses and other vehicles, it was the most powerful military force the world had yet witnessed.

This titanic struggle was to decide the fate of Nazi attempts to conquer Europe. It would be called Operation Barbarossa. One of the few large-scale German military campaigns of WWII to not be code-named after a colour, Barbarossa raged across thousands of miles of Russia, until it foundered on the borders of Asia, at Stalingrad, on the Volga river.

Strangely – for me it connects four places I have worked in – Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen north of Berlin, southern Turkey, Lebanon and what today is Volgograd.

The Barbarossa campaign reduced:

Avoid a two-front war, and don’t invade Russia were two cardinal military rules broken by Hitler in June of 1941. So why do it?

The drive behind the campaign were myriad:

Knocking out Russia as a continental ally of the UK, thus hastening a peace deal in the west. This offer had long been a hope of Hitler’s foreign policy – his offer was leaving Britain’s over-seas empire intact in return for their non-interference with Nazi hegemony in Europe.

More pressingly, the Soviet Union’s military strength and long term policy goals, though held temporarily in check by a pact with Hitler over the invasion of Poland in 1939, would only increase and threaten Germany so to attack sooner was better than later.

Resources for the war effort (particularly oil) would be a Nazi gain upon Soviet defeat.

And much longer term, the dream of creating an agricultural paradise with Nazi warrior settler families controlling huge estates exploiting local slave labour. This would produce food in abundance, sustaining the population of the huge post-war German empire. This program would also help support Hitler’s ultimate goal – a war against the US. Interestingly, during Barbarossa, Hitler spoke of this agricultural theme more than any other during his ‘down-time’ meal ‘conversations’ (generally monologues) at his HQs.

Barbarossa group think:

This dream was underpinned by a fatal hubris – the assumption that the Soviet military and the nation’s resources would eventually collapse under a maximum pressure Blitzkrieg. Amazingly – no one in Wehrmacht command applied these hypothetical conditions or outcomes to their own side.

So, by the winter of 1942/3, the attacks had stalled in the southern sphere at Stalingrad.

American lease-lend materials, the vast manpower reserves the Soviet Union could muster, the burning desire for revenge as defenders of their ravaged motherland, and a spectacularly flexible repositioned armaments sector all contributed to the turnaround.

The army with no manpower reserves, and supply deficits was now the Wehrmacht.

From 1943, the eastern front moved westwards, two years later closing, like a steel tsunami, over the Nazi capital Berlin, where it had all begun, and now came to a fiery end.

Barbarossa exposed:

After 1945, study of Operation Barbarossa revealed its terrible secrets. It was behind the smoke-screen of this campaign that one of the three phases of Holocaust occurred. The work of ‘Einzatzgruppen’ – ‘Task Forces’ murdered 1.5 million Jews in the occupied territories. Over 3 million Soviet POWs died in captivity of the German Army, countless thousands of civilians died or were dragged off west into slave labour.

But how does this campaign connect all the places listed above?

My Barbarossa:

Firstly, the name. 1941 Operation Barbarossa was named after 12thC Holy Roman Emperor Frederic 1st. Nicknamed in German ‘Rotbart’– Redbeard – it is the Italian version of this nickname that stuck – Barbarossa.

He died in 1190, ( in June too weirdly), drowning in the Göksu river near today Turkish town of Silifke. It was near here where I worked on an archaeological excavation for several seasons. On one of our days off we floated down the Göksu river in tractor inner tubes. We didn’t drown, and we named our day out ‘Barbarossa’ in Frederic’s honour.

My archaeological lecture tour circuit took me elsewhere connected with Emperor Barbarossa. After his death, many legends grew up around his mythical return. The most enduring is the story that Barbarossa sleeps under several mountains waiting to return and lead Germany to glory. The first German emperor Wilhelm I was trumpeted as his reincarnation in 1871.

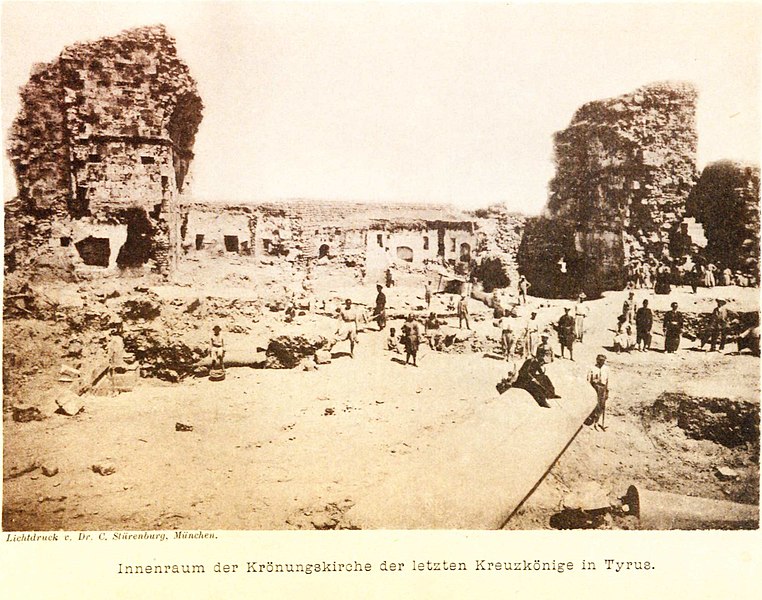

What actually happened to Barbarossa was that he was pickled. His body was put in vinegar and buried in the Crusader cathedral in the ancient city a Tyre in Lebanon. His flesh was moved to Constantinople, but his bones are said to still rest in Tyre. I often visit the ruins of this cathedral. The bones have never been found despite excavation.

All those interested in military history must visit Stalingrad. On the flat plains to the west are vast cemeteries filled with the victims of this bloodiest of battles. Bones are found regularly and reburied. The plain is still strewn with battle debris.

This is the casing of a 7.92 x 57 P25 Mauser cartridge from 1939 found on the Stalingrad battlefield. It was manufactured by Metallwarenfabrik Treuenbritzen, a place south west of Berlin. This company had manufactured munitions from the beginning of the 20thC. The Treuenbritzen munitions factory ‘Werk Selterhof’was a satellite of Concentration camp Sachsenhausen, we I often guide too. Sachsenhausen also served as the main command centre (the inspectorate) of the entire camp system from 1936.

Prisoners of war and other labourers from occupied territories worked to make these cartridges, that once spent, lay on the plains of the Volga, where the tide turned against Operation Barbarossa and changed history.

A quick internet search shows that some visitors to Berlin seemed to be disappointed with this legendary Berlin Cold War cross-roads. Not worth visiting they say. This is an outrage, no visit to Berlin is complete without crossing over Checkpoint Charlie – Berlin’s most famous intersection.

To get the best out of Checkpoint Charlie one needs to be aware of the answers to these questions:

What was Checkpoint Charlie?

Why was Checkpoint Charlie famous?

Why is Checkpoint Charlie called Charlie?

What is left of Checkpoint Charlie today?

Who could cross at Checkpoint Charlie?

Did anyone escape through Checkpoint Charlie?

Here are the answers:

What was Checkpoint Charlie?

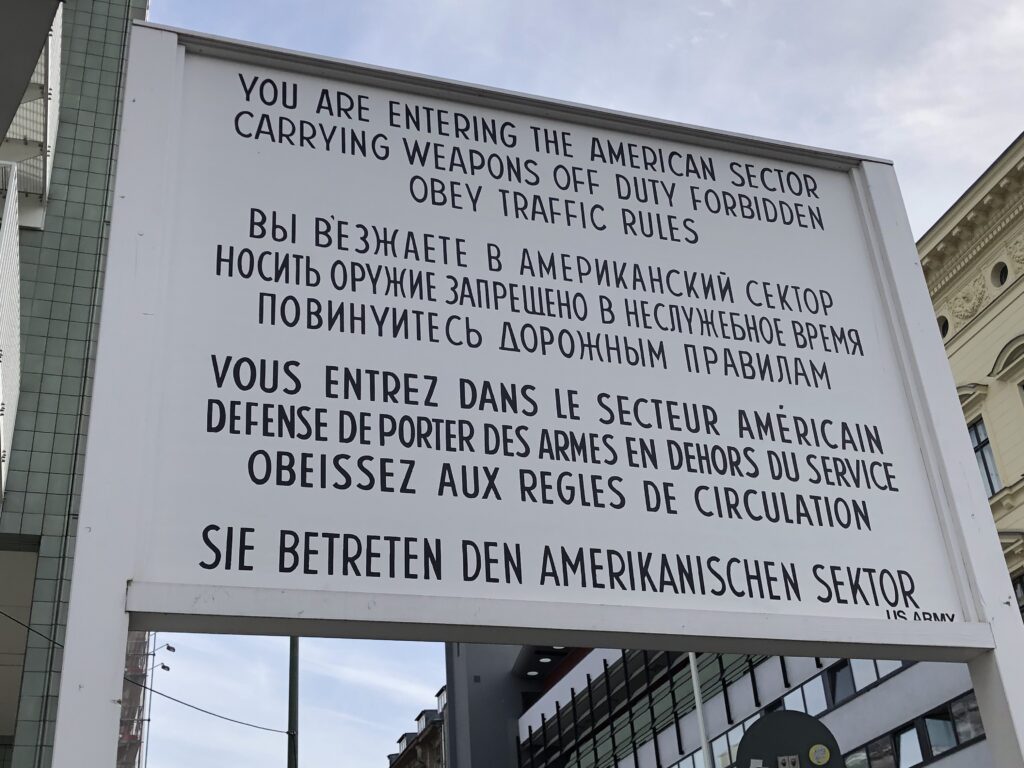

Checkpoint Charlie became the symbol of a divided Berlin, Germany and World after WWII. In reality, it was simply one of the Berlin Wall border crossings between communist east and free west Berlin, on a street corner separating the US from the Soviet sector.

This meant Checkpoint Charlie both separated and united east and west Berlin. A strange place indeed during the Cold War.

But it was also where Soviet and American troops aimed tanks and bazookas at each other during a few crisis weeks in the autumn of 1961. During those October weeks, the world stood on the brink of World War III, vividly illustrating how Berlin’s destiny held the key to Europe’s future.

Where did Checkpoint Charlie come from?

Towards the end of WWII, Germany was physically divided on paper and then afterwards these zones were occupied and controlled by the victors, Britain, the US, and the Soviet Union. Eventually France was included in this group too.

Berlin was carved up into 4 sectors too. This was achieved by lumping together groups of the city’s 20 boroughs into two halves – the Soviet and Western sectors. They became known and ‘East’ and ‘West’ Berlin.

The East got 8 districts, the West got 12. As a result, old district boundaries, some that had been lines on the city’s map for centuries (like the line of the old mediaeval city wall for example), became the new sector boundaries.

The Berlin Wall was built on these boundaries in August of 1961, so before this, for 16 years, the city was divided only by these lines. As tensions rose between each side in the 1950s, large signs appeared, warning you as you crossed the intersections from the west into the eastern zones. In the 1950s the east of Berlin was a dangerous world. Many people who had fallen foul of the Soviets disappeared.

These lines can still be seen today, marked by cobble-stones running around the west side of the city for the full length of the Berlin wall, some 160kms.

During the 1950s, nearly 20% of East Germany’s population, often young folks, escaped to the island of freedom – west Berlin. That was nearly 3 million people in total.

So, east Germany built the Berlin wall around it, to shut the back door out of communist east Germany and Europe in 1961.

Why was it called ‘Charlie’?

At the site of Checkpoint Charlie today, there is a sign commemorating the Cold War showing a Soviet soldier and a US soldier, staring into each other’s sectors. Neither of these men is called Charlie.

There were 9 border crossing point over the Berlin Wall. Checkpoint Charlie became the most famous. It was the end of a transit road from west Germany, through east Germany, giving access to West Berlin. There were 3 border crossings on the road – called A, B and C. The military alphabet names those letters Alpha, Bravo, and of course, Charlie. That’s why Checkpoint Charlie is called ‘Charlie’.

Why is Checkpoint Charlie famous?

During the Cold War, Berlin was where east met west. As information on the enemy became the key to Cold War success, in the 50s Berlin became the spy capital of the world. This caught the frightened world’s imagination and spawned the spy film genre often featuring Checkpoint Charlie. James Bond crossed in ‘Octopussy’, Harry Palmer in ‘Funeral in Berlin’, Richard Burton in ‘The spy who came in from the cold’ and most recently, Checkpoint Charlie featured in Tom Hanks ‘Bridge of Spies’.

Another reason is that as that Charlie was the place where military personnel and foreign visitors crossed, thus it became synonymous with the Berlin ‘crossing point’ despite fact there were others.

Death at Checkpoint Charlie

In 1962 there were two news stories from Checkpoint Charlie that taught the world the real human cost and meaning of the Berlin wall one year after it was built.

An escape through a tunnel, dug from the western side to rescue relatives, ended with the death of an east German border guard. Fidel Castro laid a wreath at the memorial to this event on the eastern side on the 10thanniversary in 1972.

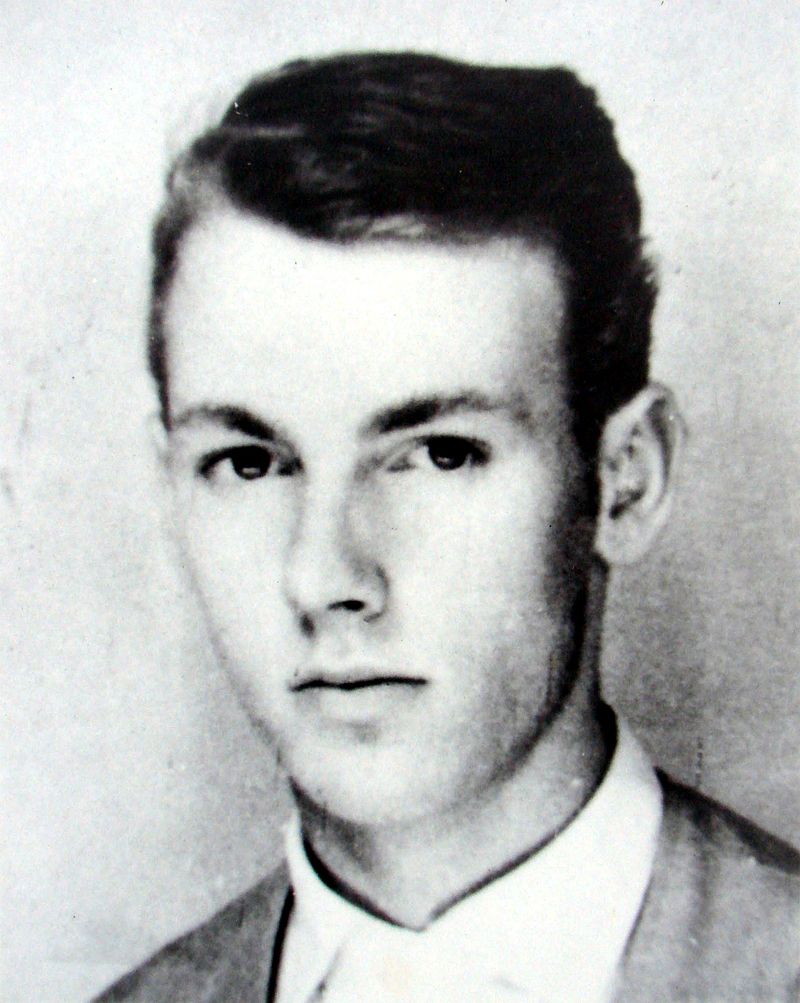

More vividly, an 18-year-old building worker called Peter Fechter was gunned down trying to escape at Checkpoint Charlie in August 1962. Shot and bleeding in the no man’s land, his death was captured on camera, filmed from the free western side, just a few metres away.

It took him 54 minutes to die.

Only then did east German border guards – those with access to the border zone (and of course with a chance to rescue Fechter and save his life) – remove his now lifeless body. The Fechter footage sent shock waves around the world. A memorial stands at the site today.

In the early phase of the wall, a man escaped through Checkpoint Charlie with friends by driving under the barrier from the eastern side. He was at the wheel of an Austin Healey Sprite, so low and streamlined, the barrier didn’t need to be raised or smashed through.

It became the popular photo-op venue for visiting politicians, defending freedom. JFK looked over the wall from the viewing platform here during his 1963 visit, famed for his ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech. Regan visited in the early 1980s too. In 1989, the removal of the US Checkpoint Charlie building itself symbolized the end of Berlin Cold War.

WWIII at Charlie – a lucky escape.

Charlie hit the headlines globally during the 1960s. Perhaps the most significant escape was the fact that World War III didn’t break out at the crossing. In 1961 when the Berlin Wall was built it threatened to block legal access from west to east. Tensions escalated until there was a terrifying tank stand-off for 3 weeks in October 1961. The Berlin crisis. The Soviets eventually backed down and the tanks withdrew.

Charlie symbolized not only the brink of nuclear war in 1961, but also the end of Cold War tensions in 1989. In the years before, a liberalizing Soviet Union had uncoupled itself from satellite states it had occupied from 1945. These (Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia) now broke away and reasserted their identities and opened their long sealed borders. East Germany, totally bankrupt, reacted to huge demonstrations in major cities by announcing on November 9th 1989 that they would do this too. That night, east Germany collapsed, East Berliners entered west Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie to jubilant crowds, and the Cold War was over. Checkpoint Charlie had changed the world.

What is Checkpoint Charlie today?

It’s a cross roads again. The desire for Berlin to move beyond the years of division and painful memories of the Wall means its redeveloped. But there are free photo exhibitions, there are museums. A copy of the sign saying ‘you are leaving the American sector‘ still stands, a copy of the border hut is still there too.

The best way to enjoy Checkpoint Charlie is to know the stories. Use your imagination as you cross, remembering, that not long ago, it was step that used to take you from one world to another, more dangerous world, where anything could happen and the future of our world was at stake.

Unsurprisingly, one of the most crowded places during Berlin’s Corona lockdown were her parks. Berlin city dwellers are lucky to have so many green spaces to choose from. Over 40% of the city is green, and there are 2,500 public parks just within the city limits. Beyond, we have the lakes and forests.

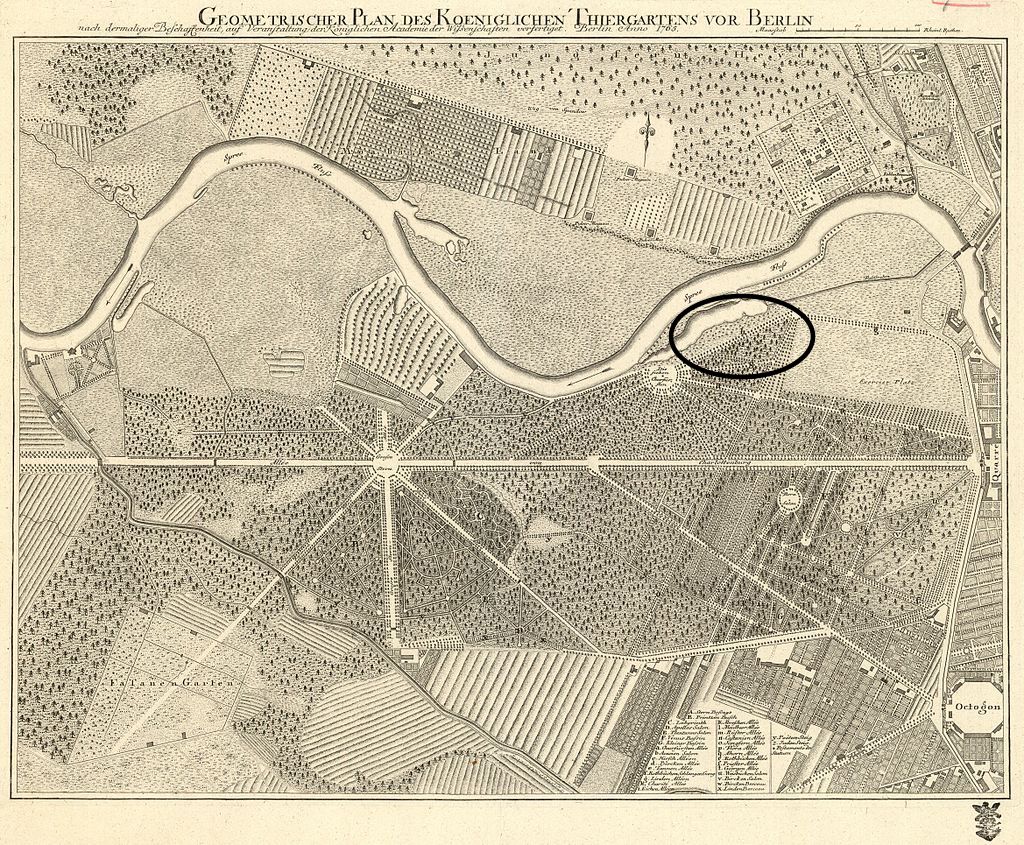

The queen of Berlin parks is the Tiergarten. This is Berlin’s green lung, originally countryside outside the Medieval city centre. It lay to the west, beyond the Brandenburg Gate, and was used first as a hunting reserve for Prussian nobility. It was traversed by sandy tracks leading to villages that one day would grow to become residential areas. After WWII, these would be known as the British sector of west Berlin .

By the late 17th century, gamekeepers were releasing hares, pheasants and deer to try their luck against hunter’s muskets and crossbows. A fine collection of these can be seen today in the German Historical Museum.

This usage gave the park its name today – the Tiergarten- lit. ‘animal garden’. It also necessitated the whole area being fenced off, and was therefore inaccessible to the general public.

This changed in the mid 1700s as the reserve was landscaped and opened to the public as a park for the first time. It was decorated with lakes and tree-lined avenues, and statues in marble and bronze. From then on, it became a crucial part of Berliners lives, up until today.

This was especially true during the Cold War period. From August 1961, it wasn’t the Tiergarten that was fenced off, but this time the entirety of the western side of the city. The Berlin Wall had been built. The ability to head out into the ‘countryside’ without having to go through an international border gave the Tiergarten a new significance for west Berliners.

Today, people wander in the park daily just as they used to over a century and a half ago. Today too, can these elements of Berlin still be witnessed, as penned in 1882 by writer Rodenburg. He says the park shows one ‘the beauties of the town, the toilets, the riches, the humour and the folly’.

Today, for those who want something more than a lawn to sunbathe, or a place to barbecue, the main attractions to be found in the Tiergarten are the Reichstag, or the Bellevue Palace and Victory column.

Now that lock-down has ended, even more folks are out and about. Strangely, there are some areas of the Tiergarten many have always passed by.

There is the forgotten section called the ‘English Garden’ with its tea house. Separated from the main body of the park by post-war rebuilding, it was gifted to the west Berliners by the British government in the late 1940’s. As the foreign minister of the UK at the time was Sir Anthony Eden, this new section became known as the ‘Garden of Eden’.

There is also another forgotten corner in the north-east that most don’t come across. This is marked by a signature post-war modern building called the Congress Hall. A strange looking building, it was designed by an American architect called Stubbins and opened in 1957. It was nick-named by the Berliners the ‘pregnant oyster’. It collapsed due to a design fault in 1980 before being reopened 9 years later. The front garden pool is graced with a sculpture ‘Split oval/butterfly’ by the legendary artist Sir Henry Moore.

Modern architecture often has weird and wonderful forms, but there is more to the story behind the design of this building. It’s supposed to remind us of a tent.

Once Prussian king Fredrick the Great had opened the park to the public, there was money to be made. So, in 1745, here on the banks of the Spree river, Berliners of Huguenot extraction, (originally coming a generation before as Protestant refugees, mainly from France) applied for and were granted licences to open refreshment tents. Here were served first drinks, and later food as well. Berlin river and lake fish were also enjoyed: Pike, Eels and Pike Perch, and even Tadpoles in beer sauce.

For the founders of this business, their way to work was short. Directly on the other side of the river was and still is the workers district of Moabit where the Huguenots had settled from 1686. Gondolas acted as water-taxis taking revellers back to this area, renowned for its pubs.

This tented area became hugely popular in the summer months, and eventually the tents were replaced by four permanent buildings, still called ‘tents’ and sponsored by breweries. This is a similar arrangement to the most famous set of ‘tents’ of all – the Munich Oktoberfest.

The area was eventually dominated by the construction of a multiplex called the Kroll Opera. The Tents, the opera and surrounding residential areas cemented the district as one of the most desirable locations in Berlin.

It was all left in ashes by the Nazi’s war. Today, its remembered by the strange form of the Congress Hall, and a short lane leading to the river. It’s still called ‘In the tents’, even today.

It’s time to put this to bed.

History is a strange animal. Having spent many years on archaeological excavations ‘creating’ it, I know the fragility of theories drawn from interpretations of what was exposed. The accepted historical narrative and its conclusions are often derived from these theories. If part of the initial theory is wayward, it still gets repeated down the line and becomes historical fact. To be sure, later, it might be reinterpreted.

One of these persistent errors still appears in the story of the plan to assassinate Hitler in 1944. I was reminded of it whilst making a short Berlin urban history film (you can watch it HERE) recently in a Berlin Kreuzberg cemetery.

Many graves in Berlin cemeteries have terracotta markers, replete with Berlin Bear, commemorating especially honoured citizens. One of these is a mass grave, holding originally 5 murdered men. They were dug up almost immediately after their burial, their bodies burned and the ashes scattered in the fetid pools of a Berlin sewage plant.

These were the men who, as leaders of the Home Army, masterminded a plot to kill Hitler in his eastern headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, in July 1944 – known to history as the Stauffenberg Bomb Plot.

All books covering the Nazi period have a chapter on resistance to the Nazi regime, from lone individuals of conscience like George Elser, brave young students like the Scholls and their White Rose movement. There were aristocrats, intellectuals and clergy members and many courageous others who took action or debated it, or fussed over the make-up of post-war Germany and Europe.

During the Nazi dictatorship, the only group that had the power to stop Hitler was the Wehrmacht – the German Army.

Within their ranks, plans to take steps against Hitler gathered pace in 1938, but only sprang into action in 1943 (when it was clear that Germany was going to lose the war – frankly, the primary drive for their taking action). Bottle bombs in Hitler’s plane, suicide bombings and shootings were planned and either failed or the attempt abandoned.

But on July 20th 1944, just before lunch, Colonel Stauffenberg would try and fail to blow Hitler up with 990 grams of explosives, during the midday conference at the Wolf’s Lair.

And it’s here the persistent error occurs.

It is this: The bomb failed to kill Hitler as the temporary meeting building was made of wood and didn’t contain the blast sufficiently to do the required damage.

There are some indications of where this error might originate. The fact that Hitler’s bunker was being reinforced at the time, and therefore he was being temporarily accommodated in the massive Guest Bunker did mean the conference venue that day was not the usual.

But it was not a wooden hut.

Photos of the destroyed interior show lots of splintered wood panelling.

Another reason perhaps for this widespread error is possibly the historical drama of the near miss, the thrill of the ‘what if’.

Still, I went through the Jacksons Berlin Tours bookshelves and found this:

Fraenkel & Manvell The July Plot

‘a hut…a room built of wood’

Baxter Wolf’s Lair

‘stuffy wooden barracks…hutments’

Ritchie Faust’s Metropolis

‘in a wooden hut’

Roper Last days of Hitler

‘had the conference taken place in the usual concrete bunker and not a wooden hut’

Kershaw Hitler Nemesis

‘wooden barrack hut inside the fence’

So, what are the facts?

The 1944 meeting room barrack was a phase one type. They were made of brick, with concrete sections above the door and window line and later reinforced. The roof itself had an additional ca. 50 cm concrete reinforced slab top. The roof line had metal ‘eyes’ from which to hang camouflage netting making the whole complex invisible from the air. The day the invasion of Russia began in 1941, the regular Berlin to Moscow flight past directly over-head, unaware.

The barrack windows were protected from the outside with green metal shutters. The interiors (all of them in the dozens of bunker complexes at the Wolf’s Lair) had pine cladding.

The thing that probably saved Hitler’s life was the fact he was leaning over the table top at the time of the explosion, the table itself deflecting much of the blast left and right. Below the wooden floor was a metre of space for a damp-course, piping and wiring. This absorbed much of the blast downwards.

And the luck of the Devil.

In mid-January 1945, with the Red Army within earshot, the Wolf’s Lair was demolished. ‘Operation Island’ used so much high explosive that the metre-thick ice on the surrounding lakes cracked from the percussion. The barracks where Stauffenberg’s bomb had exploded was also demolished. This needed dynamite too. The standard practice for the destruction of this type of object was to simply blow the walls out, allowing the roof to collapse.

The ruins of the walls and roof still lie where the demolition left them, and are still visible today. Though places of memorial like Auschwitz have added much to the science of conservation of important wooden buildings from the past, but this is not needed at the Wolf’s Lair.

Every now and then a strange phrase is uttered by German politicians, often as a warning: Sonderweg.

Literally ‘special path’ or ‘way’ it referrers to the the early 20th century independent, selfish, and shall we say, ill- advised policy decisions of a nationalist, chauvinistic Imperial Germany.

History shows us that this path led to a bloody world. The structure of the EU today is a legacy of this. Germany is bound together with other nations, all with a common policy decision making process.

Politicians sound the alarm when there is a hint of sonderweg. It’s almost as if the sonderweg is a German trait they might not be able to resist in the future, like some weird magnetism.

It could be argued WWI and WWII were a product of the sonderweg thinking. But there are dark episodes in German behaviour that occurred even before WWI.

Today, Germany has acknowledged responsibility for the genocidal war waged against tribal groups in Namibia between 1904 and 1907. It has agreed to pay over 1 billion Euro in compensation. Germany’s examination of its own more recent past makes this colonial period painfully shameful, but gives it perhaps an ability to acknowledge its mistakes more readily than other countries.

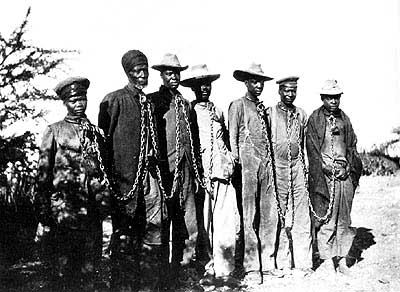

In 1897, in what was then called German Southwest Africa (now Namibia), famine and pestilence wiped out the herds of the Herero peoples. Destitute, many gravitated to German controlled farmsteads looking for a way to survive. This quickly turned them into serf slaves. By 1904 this situation had become intolerable and they rose up, only to be driven into the desert to die, or be mown down by German forces under General von Trotha, called in to fix things by Kaiser Bill. Some 60,000 Herero people perished.

There was a second Namibian tribe that was also persecuted – the Nama or Namaque. Better known in European racist jargon of the time as ‘the Hottentots’. They too were shot and incarcerate in camps where many died.

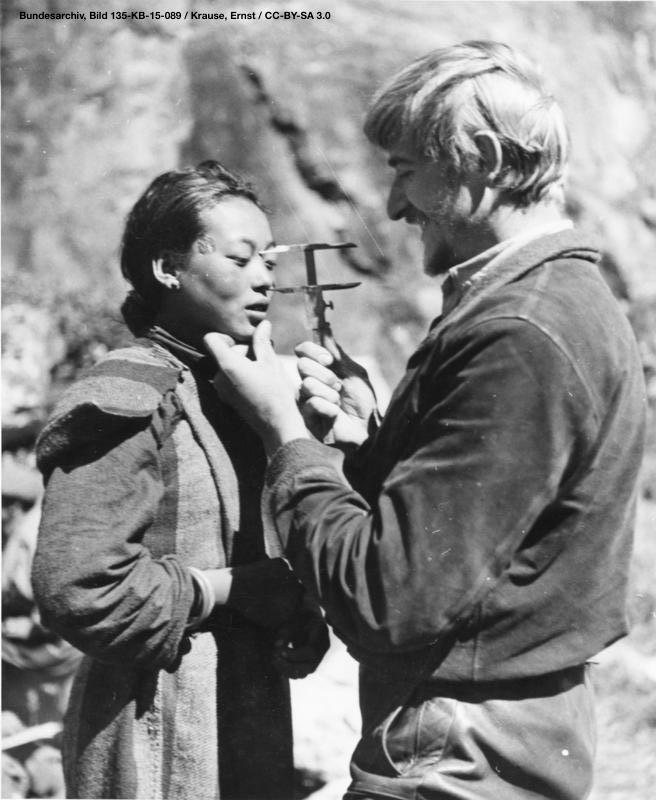

The pseudo-scientific, social-Darwinian thinking, driving and justifying racist colonial policy, was already well established globally. A repulsive legacy of the Herero killings was the forcing of surviving women to de-flesh skulls with glass shards for their preservation and transport back to Berlin. Here they could be used to advance careers at the recently founded ‘German society of racial hygiene’.

One of the men who organised this body-part trade from Namibia was called Felix von Luschan. He was an anthropologist and archaeologist, who excavated with Robert Koldewey, later famed for his Babylon discovery of the Ishtar Gate, in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum we can visit today.

These pseudo-scientific disciplines continued, and later fell easily into step with the racist polices of the Nazis.

Here the Namibian genocide surfaces again, laughably so, if it wasn’t so disgusting.

Heinrich Himmler created a department investigating the origins of Nordic ‘races’ called ‘Ahnenerbe’ – or ‘ancestral heritage’. Eventually it became a part of the main security apparatus and had offices on the Brüderstraße, next door to where Berlin is now building the House of One.

Broadly, this organisation was a gaggle of ‘academics’ bent on proving archaeologically the racial theories of the origin’s and superiority of the ‘Aryan’. Excavations and expeditions were conducted all over the world, measuring crania and noses and searching for ethnic groups who escaped the flooding of Atlantis.

One of these characters was a man called Berger, who died in 2009. After the war, he was exonerated, despite having been instrumental in the expansion of the Ahnenerbe’s skeleton collection, partly composed of Auschwitz victims.

One of the most pathetic lines of study that Beger worked on relates to Namibian genocide. It was inspired by his boss Heinrich Himmler. Himmler was interested in late Palaeolithic period ‘Venus figurines’. These are ubiquitous around Europe and the near east, represent exaggerated female forms, and are some of the earliest art work ever found.

They are intriguing, with their hints at religious beliefs, a ‘female creator’ concept. Perhaps they were for cult usage, centred around the reproductive and nurturing capacity of the female.

This was not what Himmler thought. He saw a connection between these prehistoric figurines and the Nama ‘Hottentot’ people of Namibia. Why? Because they both had large posteriors thought Himmler. Perhaps their forebears had been expelled from Europe when the master Aryan arrived?

Himmler thought on. Jewish women often had large rears too. Could they also be a prehistoric group driven from Europe by the master race? Beger investigated this ‘theory’. Yes, he thought, there seems to be connection in the posteriors ‘between Hottentots, North Africa and Near eastern peoples’. This led to a photographic study of concentration camp female Jewish prisoners for further investigation.

Many of these basic ideas of the Ahnenerbe are still currency today, amongst unpleasant or crack pot groups and conspiracy theorists. or D list documentary makers (wisdom of the pyramids type stuff).

Perhaps todays official acknowledgement of the horrors of the German state acting on racist theories a century ago in Namibia might start a path to reconciliation, and the examination and sloughing these dangerously divisive concepts.

Berlin and its surroundings offer a fine line in historic tables.

We have the desk of polymath Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Goethe, that can be seen in the Märkisches Museum.

We have the table, around which the Truman, Churchill and Stalin sat deciding the future of post-war Berlin, Germany and Europe in 1945. This can be seen in Potsdam.

And finally, there’s a table in the Berlin district of Karlshorst. This one is on show in the venue where the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany was signed by Marshall Keitel on 8th of May 1945.

But it’s not the table in Karlshorst we’re are interested in here. It’s the sculpture in the garden of what is now the German Russian Museum.

It is has featured in the garden since 2005, and is called ‘Shot-through bridge stanchion Schlüterstraße’.

Catchy.

It’s a bronze work by a Dutch artist called Jan Henderikse, and is from 1998.

The actual cannon hole and stanchion depicted in Henderikse’s piece do really exist. They can be still seen today. They are a testament to the violence of the battle for Berlin here on the 28th April 1945.

Have a look here at my short video about this Berlin battle field damage for some details and location. Then, if you’re passing – you can check it out, or I can show you on this tour

There is only one slight problem with the sculpture. It’s name.

It’s not on Schlüterstraße. It’s on the train bridge crossing Leibnitzstraße, corner of Kantstraße, admittedly only a block west.

But still a near miss.

Berlin and its surroundings offer a fine line in historic tables.

We have the desk of polymath Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Goethe, that can be seen in the Märkisches Museum.

We have the table, around which the Truman, Churchill and Stalin sat deciding the future of post-war Berlin, Germany and Europe in 1945. This can be seen in Potsdam.

And finally, there’s a table in the Berlin district of Karlshorst. This one is on show in the venue where the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany was signed by Marshall Keitel on 8th of May 1945.

But it’s not the table in Karlshorst we’re are interested in here. It’s the sculpture in the garden of what is now the German Russian Museum.

It is has featured in the garden since 2005, and is called ‘Shot-through bridge stanchion Schlüterstraße’.

Catchy.

It’s a bronze work by a Dutch artist called Jan Henderikse, and is from 1998.

The actual cannon hole and stanchion depicted in Henderikse’s piece do really exist. They can be still seen today. They are a testament to the violence of the battle for Berlin here on the 28th April 1945.

Have a look here at my short video about this Berlin battle field damage for some details and location. Then, if you’re passing – you can check it out, or I can show you on this tour

There is only one slight problem with the sculpture. It’s name.

It’s not on Schlüterstraße. It’s on the train bridge crossing Leibnitzstraße, corner of Kantstraße, admittedly only a block west.

But still a near miss.