Unsurprisingly, one of the most crowded places during Berlin’s Corona lockdown were her parks. Berlin city dwellers are lucky to have so many green spaces to choose from. Over 40% of the city is green, and there are 2,500 public parks just within the city limits. Beyond, we have the lakes and forests.

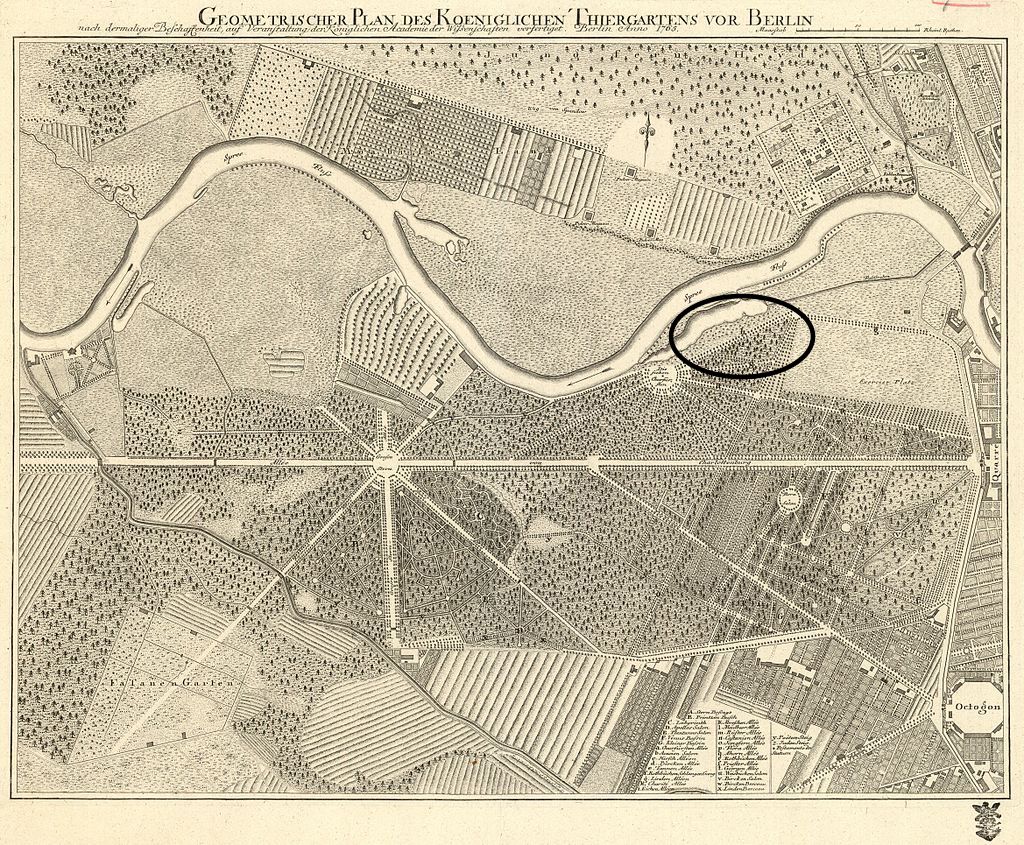

The queen of Berlin parks is the Tiergarten. This is Berlin’s green lung, originally countryside outside the Medieval city centre. It lay to the west, beyond the Brandenburg Gate, and was used first as a hunting reserve for Prussian nobility. It was traversed by sandy tracks leading to villages that one day would grow to become residential areas. After WWII, these would be known as the British sector of west Berlin .

By the late 17th century, gamekeepers were releasing hares, pheasants and deer to try their luck against hunter’s muskets and crossbows. A fine collection of these can be seen today in the German Historical Museum.

This usage gave the park its name today – the Tiergarten- lit. ‘animal garden’. It also necessitated the whole area being fenced off, and was therefore inaccessible to the general public.

This changed in the mid 1700s as the reserve was landscaped and opened to the public as a park for the first time. It was decorated with lakes and tree-lined avenues, and statues in marble and bronze. From then on, it became a crucial part of Berliners lives, up until today.

This was especially true during the Cold War period. From August 1961, it wasn’t the Tiergarten that was fenced off, but this time the entirety of the western side of the city. The Berlin Wall had been built. The ability to head out into the ‘countryside’ without having to go through an international border gave the Tiergarten a new significance for west Berliners.

Today, people wander in the park daily just as they used to over a century and a half ago. Today too, can these elements of Berlin still be witnessed, as penned in 1882 by writer Rodenburg. He says the park shows one ‘the beauties of the town, the toilets, the riches, the humour and the folly’.

Today, for those who want something more than a lawn to sunbathe, or a place to barbecue, the main attractions to be found in the Tiergarten are the Reichstag, or the Bellevue Palace and Victory column.

Now that lock-down has ended, even more folks are out and about. Strangely, there are some areas of the Tiergarten many have always passed by.

There is the forgotten section called the ‘English Garden’ with its tea house. Separated from the main body of the park by post-war rebuilding, it was gifted to the west Berliners by the British government in the late 1940’s. As the foreign minister of the UK at the time was Sir Anthony Eden, this new section became known as the ‘Garden of Eden’.

There is also another forgotten corner in the north-east that most don’t come across. This is marked by a signature post-war modern building called the Congress Hall. A strange looking building, it was designed by an American architect called Stubbins and opened in 1957. It was nick-named by the Berliners the ‘pregnant oyster’. It collapsed due to a design fault in 1980 before being reopened 9 years later. The front garden pool is graced with a sculpture ‘Split oval/butterfly’ by the legendary artist Sir Henry Moore.

Modern architecture often has weird and wonderful forms, but there is more to the story behind the design of this building. It’s supposed to remind us of a tent.

Once Prussian king Fredrick the Great had opened the park to the public, there was money to be made. So, in 1745, here on the banks of the Spree river, Berliners of Huguenot extraction, (originally coming a generation before as Protestant refugees, mainly from France) applied for and were granted licences to open refreshment tents. Here were served first drinks, and later food as well. Berlin river and lake fish were also enjoyed: Pike, Eels and Pike Perch, and even Tadpoles in beer sauce.

For the founders of this business, their way to work was short. Directly on the other side of the river was and still is the workers district of Moabit where the Huguenots had settled from 1686. Gondolas acted as water-taxis taking revellers back to this area, renowned for its pubs.

This tented area became hugely popular in the summer months, and eventually the tents were replaced by four permanent buildings, still called ‘tents’ and sponsored by breweries. This is a similar arrangement to the most famous set of ‘tents’ of all – the Munich Oktoberfest.

The area was eventually dominated by the construction of a multiplex called the Kroll Opera. The Tents, the opera and surrounding residential areas cemented the district as one of the most desirable locations in Berlin.

It was all left in ashes by the Nazi’s war. Today, its remembered by the strange form of the Congress Hall, and a short lane leading to the river. It’s still called ‘In the tents’, even today.

It’s time to put this to bed.

History is a strange animal. Having spent many years on archaeological excavations ‘creating’ it, I know the fragility of theories drawn from interpretations of what was exposed. The accepted historical narrative and its conclusions are often derived from these theories. If part of the initial theory is wayward, it still gets repeated down the line and becomes historical fact. To be sure, later, it might be reinterpreted.

One of these persistent errors still appears in the story of the plan to assassinate Hitler in 1944. I was reminded of it whilst making a short Berlin urban history film (you can watch it HERE) recently in a Berlin Kreuzberg cemetery.

Many graves in Berlin cemeteries have terracotta markers, replete with Berlin Bear, commemorating especially honoured citizens. One of these is a mass grave, holding originally 5 murdered men. They were dug up almost immediately after their burial, their bodies burned and the ashes scattered in the fetid pools of a Berlin sewage plant.

These were the men who, as leaders of the Home Army, masterminded a plot to kill Hitler in his eastern headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, in July 1944 – known to history as the Stauffenberg Bomb Plot.

All books covering the Nazi period have a chapter on resistance to the Nazi regime, from lone individuals of conscience like George Elser, brave young students like the Scholls and their White Rose movement. There were aristocrats, intellectuals and clergy members and many courageous others who took action or debated it, or fussed over the make-up of post-war Germany and Europe.

During the Nazi dictatorship, the only group that had the power to stop Hitler was the Wehrmacht – the German Army.

Within their ranks, plans to take steps against Hitler gathered pace in 1938, but only sprang into action in 1943 (when it was clear that Germany was going to lose the war – frankly, the primary drive for their taking action). Bottle bombs in Hitler’s plane, suicide bombings and shootings were planned and either failed or the attempt abandoned.

But on July 20th 1944, just before lunch, Colonel Stauffenberg would try and fail to blow Hitler up with 990 grams of explosives, during the midday conference at the Wolf’s Lair.

And it’s here the persistent error occurs.

It is this: The bomb failed to kill Hitler as the temporary meeting building was made of wood and didn’t contain the blast sufficiently to do the required damage.

There are some indications of where this error might originate. The fact that Hitler’s bunker was being reinforced at the time, and therefore he was being temporarily accommodated in the massive Guest Bunker did mean the conference venue that day was not the usual.

But it was not a wooden hut.

Photos of the destroyed interior show lots of splintered wood panelling.

Another reason perhaps for this widespread error is possibly the historical drama of the near miss, the thrill of the ‘what if’.

Still, I went through the Jacksons Berlin Tours bookshelves and found this:

Fraenkel & Manvell The July Plot

‘a hut…a room built of wood’

Baxter Wolf’s Lair

‘stuffy wooden barracks…hutments’

Ritchie Faust’s Metropolis

‘in a wooden hut’

Roper Last days of Hitler

‘had the conference taken place in the usual concrete bunker and not a wooden hut’

Kershaw Hitler Nemesis

‘wooden barrack hut inside the fence’

So, what are the facts?

The 1944 meeting room barrack was a phase one type. They were made of brick, with concrete sections above the door and window line and later reinforced. The roof itself had an additional ca. 50 cm concrete reinforced slab top. The roof line had metal ‘eyes’ from which to hang camouflage netting making the whole complex invisible from the air. The day the invasion of Russia began in 1941, the regular Berlin to Moscow flight past directly over-head, unaware.

The barrack windows were protected from the outside with green metal shutters. The interiors (all of them in the dozens of bunker complexes at the Wolf’s Lair) had pine cladding.

The thing that probably saved Hitler’s life was the fact he was leaning over the table top at the time of the explosion, the table itself deflecting much of the blast left and right. Below the wooden floor was a metre of space for a damp-course, piping and wiring. This absorbed much of the blast downwards.

And the luck of the Devil.

In mid-January 1945, with the Red Army within earshot, the Wolf’s Lair was demolished. ‘Operation Island’ used so much high explosive that the metre-thick ice on the surrounding lakes cracked from the percussion. The barracks where Stauffenberg’s bomb had exploded was also demolished. This needed dynamite too. The standard practice for the destruction of this type of object was to simply blow the walls out, allowing the roof to collapse.

The ruins of the walls and roof still lie where the demolition left them, and are still visible today. Though places of memorial like Auschwitz have added much to the science of conservation of important wooden buildings from the past, but this is not needed at the Wolf’s Lair.