In 1938, the head of the Nazi security agency and man who would later manage the Holocaust – Reinhardt Heydrich- opened a high-class brothel on a leafy, residential Berlin street.

Staffed by 20 specially selected and trained prostitutes, it catered for the elite of the Nazi party and their foreign visitors. Patrons including propaganda minister Goebbels, Mussolini’s son in law Count Ciano, the head of Hitler’s today guard regiment and Himmler’s right hand man Heydrich himself.

Named after madam Kitty Schmidt, ‘Salon Kitty’ was not just a palace of pleasure for top Axis members, but Heydrich had the venue bugged to spy on his allies who might offer information at such an indiscreet venue.

Bombed out by the end of the war, the house returned to civilian use. Today half of Salon Kitty lies empty waiting for new tenants. Recently, I gained access to the very rooms of Salon Kitty today. To see the pictures and hear the story click here .

Attempts to answer the great, universal questions can be provided by two disciplines – science and religion. The former produces a list of details on ‘how’, the latter offers theoretical options on ‘why’, in which one can place one’s faith. Or not.

The same can be said about historians and the questions of the Third Reich. The ‘why’ is still both debated and often obscene. But there is a significant and forgotten ‘how’. And its name is Franz Gürtner.

Gürtner enabled Hitler, at several crucial junctures on his road to power, to survive. Without him, Hitler would not have become Hitler.

Hindsight history is full of ‘if only’. If only more back-bone had been shown against Nazi Germany’s risky aggression during the reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936. If only Stauffenberg’s bomb had killed Hitler in 1944 and so on. Surrounding all these hypotheticals are explanations, provisions of context and mitigating circumstances, even caveats of what futures these events might have produced had the ‘right’ thing been done at the time. All this adds to the merry-go-round of historical debate.

These examples look back and identify alternative courses of action that would have produced a better world. But at the time, there was already a mechanism that could have kept the name Hitler to just a footnote of history. It was the state institution that collates rules to regulate society, behaviour and punishment for the good of the whole: The Law. If it’s clear statutes had been followed in the 1920s, Hitler would have sunk with little trace.

But in those turbulent years of Hitler’s early political career, the law wasn’t obeyed. By 1933 it was too late. Soon after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor, Germany became a county where the fair rule of law ceased to apply. Swathes of citizens whose choice of political views, or simply their ethnic heritage, clashed with the Nazis views, now fell outside its protection.

The law was now subject to Hitler’s whim. In August 1940, the German Minister for Justice himself said, in response to a local judge objecting to what was simply illegal, government sanctioned mass murder: “If you cannot recognise the will of the Führer as a source of law, then you cannot remain a judge”. This minister’s name was Franz Gürtner, the mass murder the Nazi Euthanasia program that began in September of 1939.

Gürtner was Bavarian civil servant who initially worked in the state’s Justice Ministry. In his early 30s he served with distinction in the German army during WWI. Upon his demobilization, he was absorbed back into the Justice Ministry in Munich. The political aftermath of WWII here was chaotic. His nationalist sympathies saw him become a member of the German National Peoples Party, the DNVP. Revolution in Bavaria in 1919 produced the ‘Republic of the councils’, a short lived left-wing government. This was violently over thrown by an independent army of ‘freikorps’ forces. One of the common soldiers supporting the left-wing regime was in reality a stool pigeon, who betrayed his comrades in the aftermath of the right-wing take over. This soldiers name was Adolf Hitler.

For many like Gürtner and Hitler, WWI didn’t end in 1918/19. The war continued against the young democracy – the Weimar Republic. Brutalised ex-soldiers with nothing to lose perpetrated murder after murder in their struggle against what they saw as the betrayers of Germany. The 1922 drive-by shooting of Foreign Minister Rathenow in a wealthy Berlin suburb perhaps the most well-known of these assassinations. These crimes could not go unpunished. So, in Bavaria, an official was commissioned to investigate the murders, and in a secret protocol told not to solve them. The murderers would go unpunished. This officials name was Franz Gürtner.

Hitler’s role during this chaos was as a local political celebrity, agitator and provocateur of violence. Many times, after Hitler spoke, people died. Often he had been called to account by the Bavarian state wanting to censure him for his law breaking. Hitler would grab second chances by swearing he would stop illegal activities. The dilemma was that Hitler’s party represented views that were broadly shared by the anti-democratic ‘secret army’ of demobilized soldiers now serving in positions of power in Bavaria. It was these same men that had deliberately failed to mete out justice for the political murders they silently supported.

In 1924 they had another important court case to judge in Munich, an event that had left 16 men dead.

In 1923, the traumas of the lost war and inflation was finally subsiding. Foreign financial investment was to produce several ‘good’ years. Hitler, desperate to grab a chance to increase the fear and chaos on which he thrived politically, launched his ill-fated coup d’étatin Munich in November 1923.

It failed, and as the shooting started Hitler was the first to run away. He was arrested. During the trial the prosecution had trouble looking the treasonous defendants in the eye. This is because they knew each other, worked together and supported each other. The result was a lenient sentence for Hitler. Five years. And no deportation from Germany – a fate that would have befallen any other foreigner who had behaved as Hitler had done in the years before.

The name of the man who allowed Hitler to take over the trial with his defence, and whose gavel sealed his light sentence, was Franz Gürtner.

Nine months later, Hitler was released. Whilst in prison he had become forgotten by most of his colleagues, and his movement had disintegrated. The Nazi party had been outlawed and Hitler had been banned from public speaking. But by 1926 both these bans too had been lifted. Working behind the scenes to lift both of these prohibitions, successfully, was Bavarian Justice Minister, Franz Gürtner.

By 1932 both Gürtner’s and Hitler’s stars had risen. Gürtner was now national Minister for Justice, a positon he retained when Hitler became chancellor in January 1933. He was instrumental in creating the sweeping laws for dictatorial power after the Reichstag fire, and in 1935 the infamous racial/legal code known as the Nuremberg laws. Though he did eventually attempt to mitigate against the most embarrassing and obvious Nazi perversions of law, he served in his position until his death in 1941.

Gürtner and many others believed that Germany could alleviate the shame of defeat in 1918 and reassert its destiny as a world power by ridding itself of ‘weak’ democracy and replacing it with a strong dictatorship to correct the national course. To achieve this quickly they were prepared that the law, something they had studied and represented, might have to be bent in the short term.

Alas, it was this deal that Gürtner and millions of other Germans were prepared to accept to assuage their adolescent rage at the realities resulting from national hubris and stupidity before and after WWI. Even though Gürtner died before witnessing the full harvest of what he had helped sow, he must have realized that the bargain had turned sour. WWII itself was part of this deal. It was during this phase that Gürtner’s actions led to his country and huge swathes of the world being turned into a charred hell-scape, where millions died.

Gürtner and others were familiar, I’m sure, with the work of enlightenment philosopher John Locke. He wrote: ‘Wherever law ends, Tyranny begins’. Men like Gürtners willingness, particularly those that represented the law and the Justice Ministry of the German government, to ‘work towards the Fuhrer’ after 1933, bear a special responsibility for the horrors that they went out of their way to enable.

No Hitler – no Holocaust.

No Gürtner – No Hitler.

#OTD in 1941 the German Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union. With around 3.3 million troops, and 6.6 thousand tanks and aircraft, and supported by over a million horses and other vehicles, it was the most powerful military force the world had yet witnessed.

This titanic struggle was to decide the fate of Nazi attempts to conquer Europe. It would be called Operation Barbarossa. One of the few large-scale German military campaigns of WWII to not be code-named after a colour, Barbarossa raged across thousands of miles of Russia, until it foundered on the borders of Asia, at Stalingrad, on the Volga river.

Strangely – for me it connects four places I have worked in – Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen north of Berlin, southern Turkey, Lebanon and what today is Volgograd.

The Barbarossa campaign reduced:

Avoid a two-front war, and don’t invade Russia were two cardinal military rules broken by Hitler in June of 1941. So why do it?

The drive behind the campaign were myriad:

Knocking out Russia as a continental ally of the UK, thus hastening a peace deal in the west. This offer had long been a hope of Hitler’s foreign policy – his offer was leaving Britain’s over-seas empire intact in return for their non-interference with Nazi hegemony in Europe.

More pressingly, the Soviet Union’s military strength and long term policy goals, though held temporarily in check by a pact with Hitler over the invasion of Poland in 1939, would only increase and threaten Germany so to attack sooner was better than later.

Resources for the war effort (particularly oil) would be a Nazi gain upon Soviet defeat.

And much longer term, the dream of creating an agricultural paradise with Nazi warrior settler families controlling huge estates exploiting local slave labour. This would produce food in abundance, sustaining the population of the huge post-war German empire. This program would also help support Hitler’s ultimate goal – a war against the US. Interestingly, during Barbarossa, Hitler spoke of this agricultural theme more than any other during his ‘down-time’ meal ‘conversations’ (generally monologues) at his HQs.

Barbarossa group think:

This dream was underpinned by a fatal hubris – the assumption that the Soviet military and the nation’s resources would eventually collapse under a maximum pressure Blitzkrieg. Amazingly – no one in Wehrmacht command applied these hypothetical conditions or outcomes to their own side.

So, by the winter of 1942/3, the attacks had stalled in the southern sphere at Stalingrad.

American lease-lend materials, the vast manpower reserves the Soviet Union could muster, the burning desire for revenge as defenders of their ravaged motherland, and a spectacularly flexible repositioned armaments sector all contributed to the turnaround.

The army with no manpower reserves, and supply deficits was now the Wehrmacht.

From 1943, the eastern front moved westwards, two years later closing, like a steel tsunami, over the Nazi capital Berlin, where it had all begun, and now came to a fiery end.

Barbarossa exposed:

After 1945, study of Operation Barbarossa revealed its terrible secrets. It was behind the smoke-screen of this campaign that one of the three phases of Holocaust occurred. The work of ‘Einzatzgruppen’ – ‘Task Forces’ murdered 1.5 million Jews in the occupied territories. Over 3 million Soviet POWs died in captivity of the German Army, countless thousands of civilians died or were dragged off west into slave labour.

But how does this campaign connect all the places listed above?

My Barbarossa:

Firstly, the name. 1941 Operation Barbarossa was named after 12thC Holy Roman Emperor Frederic 1st. Nicknamed in German ‘Rotbart’– Redbeard – it is the Italian version of this nickname that stuck – Barbarossa.

He died in 1190, ( in June too weirdly), drowning in the Göksu river near today Turkish town of Silifke. It was near here where I worked on an archaeological excavation for several seasons. On one of our days off we floated down the Göksu river in tractor inner tubes. We didn’t drown, and we named our day out ‘Barbarossa’ in Frederic’s honour.

My archaeological lecture tour circuit took me elsewhere connected with Emperor Barbarossa. After his death, many legends grew up around his mythical return. The most enduring is the story that Barbarossa sleeps under several mountains waiting to return and lead Germany to glory. The first German emperor Wilhelm I was trumpeted as his reincarnation in 1871.

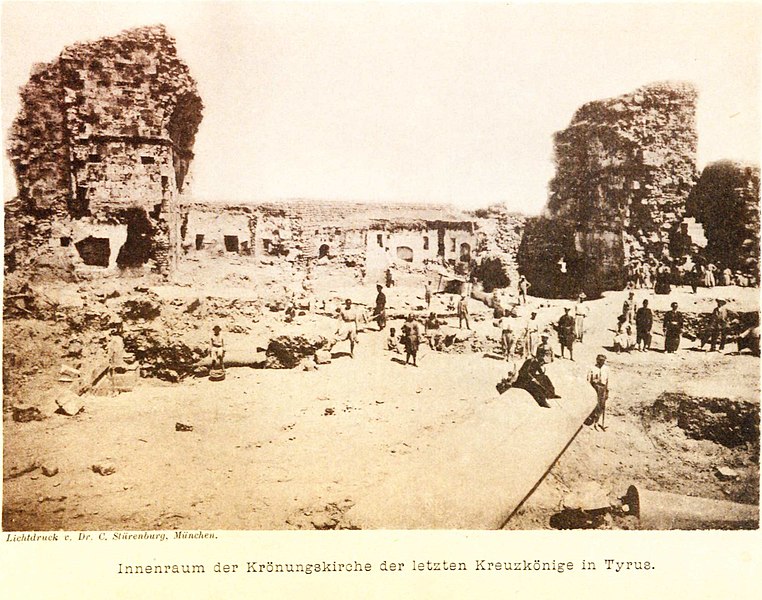

What actually happened to Barbarossa was that he was pickled. His body was put in vinegar and buried in the Crusader cathedral in the ancient city a Tyre in Lebanon. His flesh was moved to Constantinople, but his bones are said to still rest in Tyre. I often visit the ruins of this cathedral. The bones have never been found despite excavation.

All those interested in military history must visit Stalingrad. On the flat plains to the west are vast cemeteries filled with the victims of this bloodiest of battles. Bones are found regularly and reburied. The plain is still strewn with battle debris.

This is the casing of a 7.92 x 57 P25 Mauser cartridge from 1939 found on the Stalingrad battlefield. It was manufactured by Metallwarenfabrik Treuenbritzen, a place south west of Berlin. This company had manufactured munitions from the beginning of the 20thC. The Treuenbritzen munitions factory ‘Werk Selterhof’was a satellite of Concentration camp Sachsenhausen, we I often guide too. Sachsenhausen also served as the main command centre (the inspectorate) of the entire camp system from 1936.

Prisoners of war and other labourers from occupied territories worked to make these cartridges, that once spent, lay on the plains of the Volga, where the tide turned against Operation Barbarossa and changed history.

Anti-Semitism has a very long pedigree. Often, when one reads about gravestones being damaged in this context, it is Jewish headstones that have been targeted. This story is different.

The relationship with its Jewish community will forever be part of Berlin’s story. It is on the whole, a very ugly story, everywhere.

Today, Berlin’s monuments, exhibitions and study centres to this history are rather admirable. Here and there around the city are also reminders, tiny pin pricks of light in that deep, 12-year darkness as Hitler’s capital, that hint too at ‘what if?’ or ‘if only.’

The removal of reminders of uncomfortable history is an ongoing and contentious debate globally. Retrospective re-evaluations of the past often seem ignorant, lacking and lazy. The genuine relic, however uncomfortable the story it represents, cements authenticity and becomes a core around which discussion, fact and understanding can be built today.

Berlin has tussled with this debate, perhaps more intensely than other cities.

A Berlin metro station name came up for review recently. The station’s name – Möhrenstrs – or ‘Moor Street’ was the issue. No longer acceptable said some in today’s Berlin. This story has drifted from the front pages now, after a few new name proposals foundered. But if you missed the story here it is.

Berlin street names have been changed more often than most cities. Imperial period names morphed into Nazi. Then after World War II, both east and west Berlin relaunched with their own labels, and now there are some new modern ones too. It is a terrible irony that one of the longest lasting street names is Jüdenstrs, Jews Street, now both a testament and an accusation, and still signposted in the Berlin medieval period city centre area today.

One street name controversy that has rumbled for years, and seems pretty simple to resolve but hasn’t been, is Heinrich von Treitschke Straße. My daughter’s school was on this road.

He was an individual with unpleasant ideas, who lived in a time when many already knew better. Treitschke was quoted by the Nazi regime – if fact his quote appeared as a slogan on a newspaper front page every week, then available in all good Nazi newsagents near you – from 1923 until February 1945.

The name of the repulsive paper was the ‘Der Stürmer’, the content a slop of violent anti-Semitism and brutal adolescent pornography . The phrase was at the bottom of the front page was: ‘The Jews are our misfortune’

Violent antisemitism and brutal, emotionally adolescent violent pornographic fantasy sums up the Nietzschean ‘mass man’ that characterised many a the Nazi follower cum perpetrator. Godless, lawless, boorish, basic, childish, savage and completely unable to see their own degradation.

This should be born in mind when pondering today Hitler’s seemingly inexplicable appeal. The cheering masses in the beer halls, Hitler’s audience, where these folks.

Even the more erudite audience members experienced something peculiar. The German population, traumatised by the end of WWI and the myriad disasters of the 1920s, sought succour increasingly desperately, and in increasingly fringe places.

That is why Hitler was so effective. Millions of Germans abandoned the rational, the fair, and the logical and responded with a leap of faith to the emotional and self-interested, wallowing in dreams of revenge and the ecstatic vision of Hitler’s ‘quick fix’ redemption offer.

All you had to do was believe. Hitler’s speeches weren’t interesting, they were moving.

In this type of atmosphere emotive slogans and images wield power.

Hence the effectiveness of the phrase ‘the Jews are our misfortune’

Treitschke was a product of the main streams of German consciousness of the mid 1800s. As a member of parliament in the Reichstag he represented German nationalist parties and views. He was a contributor to a world into which Hitler was born. Treitschke is also quoted thus: ‘Brave peoples expand, inferior peoples perish’. This could easily have come from the Führer himself.

Where did these come from? Post French Revolution democratic fervour had spilled over into Germany by the mid 19thcentury. Industrialisation had produced a new, educated middle class that wanted representation. The workers and farmers too felt ripped off. The ruling aristocratic castes were afraid.

This catalysed debates about a new German democracy, nationalism, and imperial ambitions, often underpinned by crude notions of social Darwinism. Unfortunately, at this time, German Jewish emancipation was up for debate (again). There was also the sudden realisation that modern industrial economies and stock markets could fail. It was a new world in which some German Jews, brave and innovative, excelled. It’s failures demanded scapegoats.

These sentiments, combined eventually with broad feelings of national self-pity, jealousy (v. Treitschke was vocally anti British empire) and stupidity, contributed to the slide into World War I.

v. Treitschke died in 1896, not seeing that that he had in part inspired (the question of whether he would have been moved by Hitler’s speeches is moot as he was deaf).

He was buried in the St Matthews cemetery in Berlin, a resting place of more illustrious dead, perhaps these men are the most significant. Treitschke was a well-known figure, and his grave is substantial, made up of a costly, black-green granite head stone and flat grave-cover slab.

But today, if you look closely at this grave, you see now see something peculiar.

On the flat gravestone, under his name and dates, there are two carved scrolls. These remains untouched, and might have originally flanked a central symbol, perhaps an Iron Cross.

But at some point, probably in the 1980s, this part of the slab was ground down by persons unknown, mechanically, leaving the central section smooth and shiny. And then, with power tools, a neat star of David has been cut into the space. It’s deep and carefully executed. Only the left-hand angles seem a bit ‘off’. This hints that this person was perhaps not a professional, was determined (it’s cut into granite) and perhaps was working hurriedly as one would expect if one had lugged power tools, and a power source into a cemetery to amend a grave.

Who did this is remains a mystery. Why is pretty obvious. It looks like the ‘amendment’ will stay there as long as the grave. A strange victory.

The women who blew up Berlin.

Walk down any Berlin main street and you will be struck by its discordant architecture.

Today’s new 21st century glass and steel cages, still retaining the same mass as the rare surrounding surviving pre-war blocks, now fill the old vacant spaces left by WWII and the rare stone, bullet scarred facades of pre-1945 Berlin.

In between comes the bulk of ’50s and ’60s concrete boxes, the face of the Berlin’s great (and still ongoing) post-war relaunch. These were erected fast and cheaply, once the bombing rubble had been cleared away, to house tomorrows world. Symbolically, this fresh, modern style was chosen to represent a future in what was then the most important city in Europe.

These post-war buildings would become the faces of two choices of future, one in east Berlin and one in the west – a future under either communism or democracy.

Students of architecture would have sensed a continuity in this post-war city-wide style. It retained elements of the earlier architectural projects that fell under the broad label ‘Modernism’.

This early 20th century architecture was characterised by a shedding of historic styles, as a rapidly changing 19th century Germany industrialised, mechanised, urbanised and democratised. This new world demanded a New Berlin. Old Germany disintegrated, perishing as horse drawn Imperial carriages were replaced by electric mass public transport vehicles processing through Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate. This transition was so profound its fall-out dictated world history for the following century.

After WWII, the famed ‘Rubble Women’ cleared broken Berlin by hand, creating the ‘rubble mountains’ on both sides of the city. But one women was a different type of rubble women. She didn’t remove it. She created it. Her name was Hertha Bahr. And she blew up bits of Berlin.

There are very few images of Frau Bahr. She appears in broadcast of TV news in mid-July 1957. Berlin was still in ruins, and there amongst them is Hertha, surrounded by gangs of grinning men overalls. She is definately in charge. And she is laying charges as the footage cuts to here inserting dynamite into bore holes. Minutes later, the vast, ruined temple of industry, Lehrter Bahnhof (now Berlin Main Station), crashes to the ground.

Hertha Bahr was Germany’s first female demolition expert. Her company base was a renovated villa in the wealthy Grunewald district. Here she organised her operations. In the late 1940’s an eye witness account mentions her company involved in the demolition of buildings surrounding the famous Baroque Gendarmenmarkt Square in central Berlin.

All reports on Behr’s activities (admittedly a novelty), often seem obsessed with her appearance. This time it’s noted, she was sporting a ‘green silk blouse and red nail polish’. While she was at work here, folks were squatting in the rubble and cellars and refused to leave. One was nearly crushed by a falling wall.

Bahr’s first major commission was to destroy the building at the very heart of Hitler’s Berlin – the New Reich Chancellery from 1939. This project was a central part of the ‘denazifaction’ policy introduced by the victors in the late 1940s. Part of this ‘deprogramming’ was to remove Nazi period buildings to avoid them, in defeat, becoming places of sentimental memory of the Nazi regime. This was deemed necessary, its reported that tearful crowds gathered and sung outside the Chacellery in the immediate post war years. Even the wall plaster of Hitler’s mountain house was removed by locals as ‘the Führers breath had condensed in it’).

Though Hitler spent more time making key decisions and directing WWII from 2 other places than the Berlin Reich Chancellery (these were the ‘Wolfs Lair’ in Eastern Poland today and his ‘home’ – the Berghof – in Berchtesgaden – roughly 1000 days spent in each place) this building symbolised the core of his regime in the Nazi capital. Here was his office, and in the garden of the building his body would burn in 1945.

History does not record what she was wearing during this operation, (but it seems to have been a dark, roughish coat and black skirt).

In the late 1950s she destroyed Lehrter Station, and in the summer of 1960 the remains of Anhalter Station, leaving the entrance façade as a reminder of the ruins of war, perhaps a response to growing resistance amongst west Berliners that reminders of old west Berlin were practically all gone.

She was still working in west Berlin the 1970s, removing the ruins of domestic buildings for redevelopment, appearing in action depressing the plunger of a detonator in an article in the Carlisle Citizen newspaper based in Iowa. A white summer dress was apparently the choice here.

They quote her: ‘Blowing up a building is a safe as crossing the road, as long as you know what you are doing’.