Unsurprisingly, one of the most crowded places during Berlin’s Corona lockdown were her parks. Berlin city dwellers are lucky to have so many green spaces to choose from. Over 40% of the city is green, and there are 2,500 public parks just within the city limits. Beyond, we have the lakes and forests.

The queen of Berlin parks is the Tiergarten. This is Berlin’s green lung, originally countryside outside the Medieval city centre. It lay to the west, beyond the Brandenburg Gate, and was used first as a hunting reserve for Prussian nobility. It was traversed by sandy tracks leading to villages that one day would grow to become residential areas. After WWII, these would be known as the British sector of west Berlin .

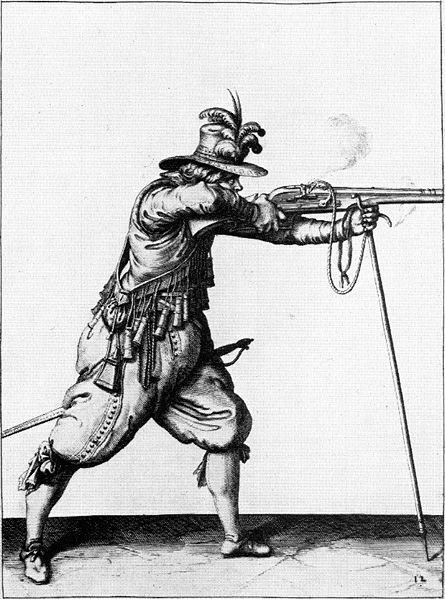

By the late 17th century, gamekeepers were releasing hares, pheasants and deer to try their luck against hunter’s muskets and crossbows. A fine collection of these can be seen today in the German Historical Museum.

This usage gave the park its name today – the Tiergarten- lit. ‘animal garden’. It also necessitated the whole area being fenced off, and was therefore inaccessible to the general public.

This changed in the mid 1700s as the reserve was landscaped and opened to the public as a park for the first time. It was decorated with lakes and tree-lined avenues, and statues in marble and bronze. From then on, it became a crucial part of Berliners lives, up until today.

This was especially true during the Cold War period. From August 1961, it wasn’t the Tiergarten that was fenced off, but this time the entirety of the western side of the city. The Berlin Wall had been built. The ability to head out into the ‘countryside’ without having to go through an international border gave the Tiergarten a new significance for west Berliners.

Today, people wander in the park daily just as they used to over a century and a half ago. Today too, can these elements of Berlin still be witnessed, as penned in 1882 by writer Rodenburg. He says the park shows one ‘the beauties of the town, the toilets, the riches, the humour and the folly’.

Today, for those who want something more than a lawn to sunbathe, or a place to barbecue, the main attractions to be found in the Tiergarten are the Reichstag, or the Bellevue Palace and Victory column.

Now that lock-down has ended, even more folks are out and about. Strangely, there are some areas of the Tiergarten many have always passed by.

There is the forgotten section called the ‘English Garden’ with its tea house. Separated from the main body of the park by post-war rebuilding, it was gifted to the west Berliners by the British government in the late 1940’s. As the foreign minister of the UK at the time was Sir Anthony Eden, this new section became known as the ‘Garden of Eden’.

There is also another forgotten corner in the north-east that most don’t come across. This is marked by a signature post-war modern building called the Congress Hall. A strange looking building, it was designed by an American architect called Stubbins and opened in 1957. It was nick-named by the Berliners the ‘pregnant oyster’. It collapsed due to a design fault in 1980 before being reopened 9 years later. The front garden pool is graced with a sculpture ‘Split oval/butterfly’ by the legendary artist Sir Henry Moore.

Modern architecture often has weird and wonderful forms, but there is more to the story behind the design of this building. It’s supposed to remind us of a tent.

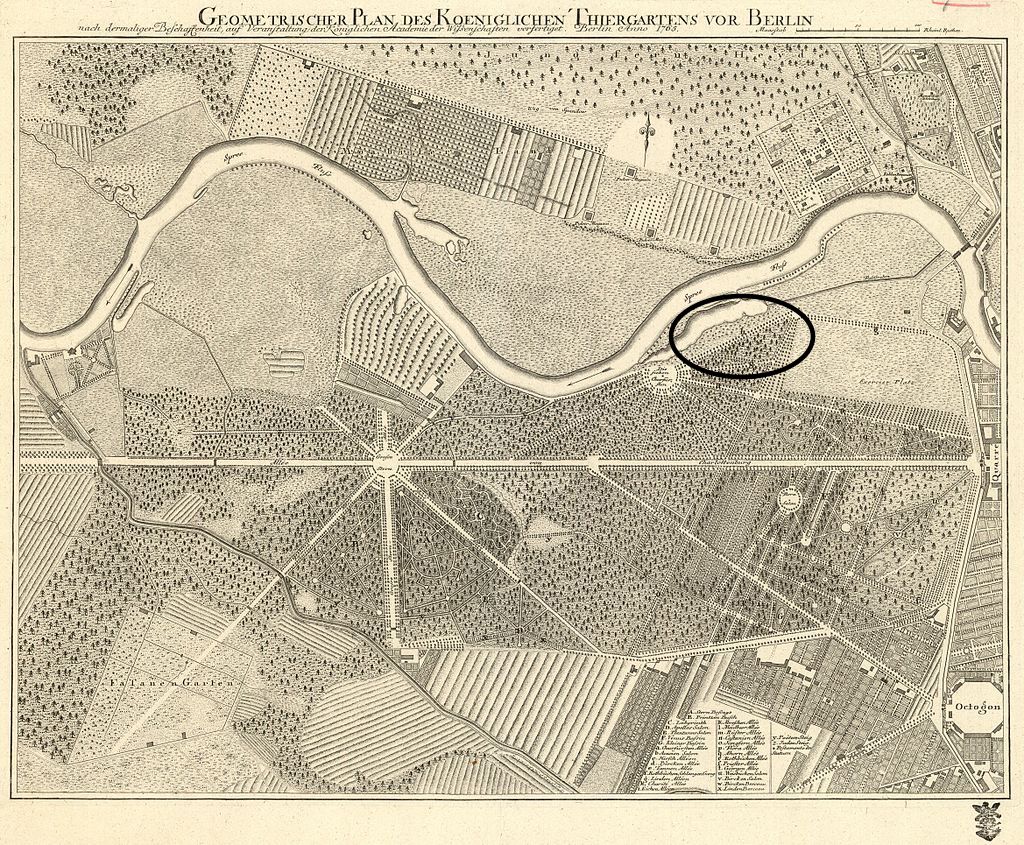

Once Prussian king Fredrick the Great had opened the park to the public, there was money to be made. So, in 1745, here on the banks of the Spree river, Berliners of Huguenot extraction, (originally coming a generation before as Protestant refugees, mainly from France) applied for and were granted licences to open refreshment tents. Here were served first drinks, and later food as well. Berlin river and lake fish were also enjoyed: Pike, Eels and Pike Perch, and even Tadpoles in beer sauce.

For the founders of this business, their way to work was short. Directly on the other side of the river was and still is the workers district of Moabit where the Huguenots had settled from 1686. Gondolas acted as water-taxis taking revellers back to this area, renowned for its pubs.

This tented area became hugely popular in the summer months, and eventually the tents were replaced by four permanent buildings, still called ‘tents’ and sponsored by breweries. This is a similar arrangement to the most famous set of ‘tents’ of all – the Munich Oktoberfest.

The area was eventually dominated by the construction of a multiplex called the Kroll Opera. The Tents, the opera and surrounding residential areas cemented the district as one of the most desirable locations in Berlin.

It was all left in ashes by the Nazi’s war. Today, its remembered by the strange form of the Congress Hall, and a short lane leading to the river. It’s still called ‘In the tents’, even today.

It’s time to put this to bed.

History is a strange animal. Having spent many years on archaeological excavations ‘creating’ it, I know the fragility of theories drawn from interpretations of what was exposed. The accepted historical narrative and its conclusions are often derived from these theories. If part of the initial theory is wayward, it still gets repeated down the line and becomes historical fact. To be sure, later, it might be reinterpreted.

One of these persistent errors still appears in the story of the plan to assassinate Hitler in 1944. I was reminded of it whilst making a short Berlin urban history film (you can watch it HERE) recently in a Berlin Kreuzberg cemetery.

Many graves in Berlin cemeteries have terracotta markers, replete with Berlin Bear, commemorating especially honoured citizens. One of these is a mass grave, holding originally 5 murdered men. They were dug up almost immediately after their burial, their bodies burned and the ashes scattered in the fetid pools of a Berlin sewage plant.

These were the men who, as leaders of the Home Army, masterminded a plot to kill Hitler in his eastern headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, in July 1944 – known to history as the Stauffenberg Bomb Plot.

All books covering the Nazi period have a chapter on resistance to the Nazi regime, from lone individuals of conscience like George Elser, brave young students like the Scholls and their White Rose movement. There were aristocrats, intellectuals and clergy members and many courageous others who took action or debated it, or fussed over the make-up of post-war Germany and Europe.

During the Nazi dictatorship, the only group that had the power to stop Hitler was the Wehrmacht – the German Army.

Within their ranks, plans to take steps against Hitler gathered pace in 1938, but only sprang into action in 1943 (when it was clear that Germany was going to lose the war – frankly, the primary drive for their taking action). Bottle bombs in Hitler’s plane, suicide bombings and shootings were planned and either failed or the attempt abandoned.

But on July 20th 1944, just before lunch, Colonel Stauffenberg would try and fail to blow Hitler up with 990 grams of explosives, during the midday conference at the Wolf’s Lair.

And it’s here the persistent error occurs.

It is this: The bomb failed to kill Hitler as the temporary meeting building was made of wood and didn’t contain the blast sufficiently to do the required damage.

There are some indications of where this error might originate. The fact that Hitler’s bunker was being reinforced at the time, and therefore he was being temporarily accommodated in the massive Guest Bunker did mean the conference venue that day was not the usual.

But it was not a wooden hut.

Photos of the destroyed interior show lots of splintered wood panelling.

Another reason perhaps for this widespread error is possibly the historical drama of the near miss, the thrill of the ‘what if’.

Still, I went through the Jacksons Berlin Tours bookshelves and found this:

Fraenkel & Manvell The July Plot

‘a hut…a room built of wood’

Baxter Wolf’s Lair

‘stuffy wooden barracks…hutments’

Ritchie Faust’s Metropolis

‘in a wooden hut’

Roper Last days of Hitler

‘had the conference taken place in the usual concrete bunker and not a wooden hut’

Kershaw Hitler Nemesis

‘wooden barrack hut inside the fence’

So, what are the facts?

The 1944 meeting room barrack was a phase one type. They were made of brick, with concrete sections above the door and window line and later reinforced. The roof itself had an additional ca. 50 cm concrete reinforced slab top. The roof line had metal ‘eyes’ from which to hang camouflage netting making the whole complex invisible from the air. The day the invasion of Russia began in 1941, the regular Berlin to Moscow flight past directly over-head, unaware.

The barrack windows were protected from the outside with green metal shutters. The interiors (all of them in the dozens of bunker complexes at the Wolf’s Lair) had pine cladding.

The thing that probably saved Hitler’s life was the fact he was leaning over the table top at the time of the explosion, the table itself deflecting much of the blast left and right. Below the wooden floor was a metre of space for a damp-course, piping and wiring. This absorbed much of the blast downwards.

And the luck of the Devil.

In mid-January 1945, with the Red Army within earshot, the Wolf’s Lair was demolished. ‘Operation Island’ used so much high explosive that the metre-thick ice on the surrounding lakes cracked from the percussion. The barracks where Stauffenberg’s bomb had exploded was also demolished. This needed dynamite too. The standard practice for the destruction of this type of object was to simply blow the walls out, allowing the roof to collapse.

The ruins of the walls and roof still lie where the demolition left them, and are still visible today. Though places of memorial like Auschwitz have added much to the science of conservation of important wooden buildings from the past, but this is not needed at the Wolf’s Lair.

Every now and then a strange phrase is uttered by German politicians, often as a warning: Sonderweg.

Literally ‘special path’ or ‘way’ it referrers to the the early 20th century independent, selfish, and shall we say, ill- advised policy decisions of a nationalist, chauvinistic Imperial Germany.

History shows us that this path led to a bloody world. The structure of the EU today is a legacy of this. Germany is bound together with other nations, all with a common policy decision making process.

Politicians sound the alarm when there is a hint of sonderweg. It’s almost as if the sonderweg is a German trait they might not be able to resist in the future, like some weird magnetism.

It could be argued WWI and WWII were a product of the sonderweg thinking. But there are dark episodes in German behaviour that occurred even before WWI.

Today, Germany has acknowledged responsibility for the genocidal war waged against tribal groups in Namibia between 1904 and 1907. It has agreed to pay over 1 billion Euro in compensation. Germany’s examination of its own more recent past makes this colonial period painfully shameful, but gives it perhaps an ability to acknowledge its mistakes more readily than other countries.

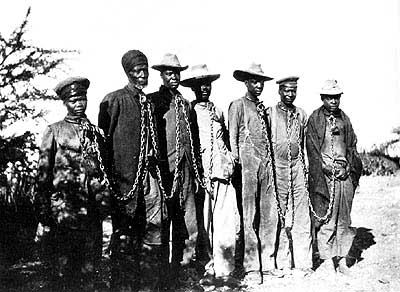

In 1897, in what was then called German Southwest Africa (now Namibia), famine and pestilence wiped out the herds of the Herero peoples. Destitute, many gravitated to German controlled farmsteads looking for a way to survive. This quickly turned them into serf slaves. By 1904 this situation had become intolerable and they rose up, only to be driven into the desert to die, or be mown down by German forces under General von Trotha, called in to fix things by Kaiser Bill. Some 60,000 Herero people perished.

There was a second Namibian tribe that was also persecuted – the Nama or Namaque. Better known in European racist jargon of the time as ‘the Hottentots’. They too were shot and incarcerate in camps where many died.

The pseudo-scientific, social-Darwinian thinking, driving and justifying racist colonial policy, was already well established globally. A repulsive legacy of the Herero killings was the forcing of surviving women to de-flesh skulls with glass shards for their preservation and transport back to Berlin. Here they could be used to advance careers at the recently founded ‘German society of racial hygiene’.

One of the men who organised this body-part trade from Namibia was called Felix von Luschan. He was an anthropologist and archaeologist, who excavated with Robert Koldewey, later famed for his Babylon discovery of the Ishtar Gate, in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum we can visit today.

These pseudo-scientific disciplines continued, and later fell easily into step with the racist polices of the Nazis.

Here the Namibian genocide surfaces again, laughably so, if it wasn’t so disgusting.

Heinrich Himmler created a department investigating the origins of Nordic ‘races’ called ‘Ahnenerbe’ – or ‘ancestral heritage’. Eventually it became a part of the main security apparatus and had offices on the Brüderstraße, next door to where Berlin is now building the House of One.

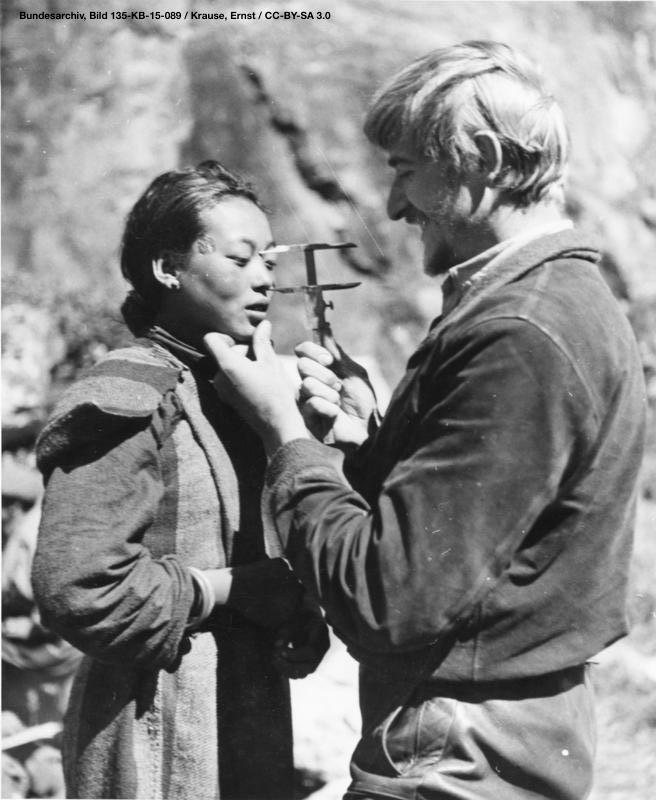

Broadly, this organisation was a gaggle of ‘academics’ bent on proving archaeologically the racial theories of the origin’s and superiority of the ‘Aryan’. Excavations and expeditions were conducted all over the world, measuring crania and noses and searching for ethnic groups who escaped the flooding of Atlantis.

One of these characters was a man called Berger, who died in 2009. After the war, he was exonerated, despite having been instrumental in the expansion of the Ahnenerbe’s skeleton collection, partly composed of Auschwitz victims.

One of the most pathetic lines of study that Beger worked on relates to Namibian genocide. It was inspired by his boss Heinrich Himmler. Himmler was interested in late Palaeolithic period ‘Venus figurines’. These are ubiquitous around Europe and the near east, represent exaggerated female forms, and are some of the earliest art work ever found.

They are intriguing, with their hints at religious beliefs, a ‘female creator’ concept. Perhaps they were for cult usage, centred around the reproductive and nurturing capacity of the female.

This was not what Himmler thought. He saw a connection between these prehistoric figurines and the Nama ‘Hottentot’ people of Namibia. Why? Because they both had large posteriors thought Himmler. Perhaps their forebears had been expelled from Europe when the master Aryan arrived?

Himmler thought on. Jewish women often had large rears too. Could they also be a prehistoric group driven from Europe by the master race? Beger investigated this ‘theory’. Yes, he thought, there seems to be connection in the posteriors ‘between Hottentots, North Africa and Near eastern peoples’. This led to a photographic study of concentration camp female Jewish prisoners for further investigation.

Many of these basic ideas of the Ahnenerbe are still currency today, amongst unpleasant or crack pot groups and conspiracy theorists. or D list documentary makers (wisdom of the pyramids type stuff).

Perhaps todays official acknowledgement of the horrors of the German state acting on racist theories a century ago in Namibia might start a path to reconciliation, and the examination and sloughing these dangerously divisive concepts.

Berlin and its surroundings offer a fine line in historic tables.

We have the desk of polymath Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Goethe, that can be seen in the Märkisches Museum.

We have the table, around which the Truman, Churchill and Stalin sat deciding the future of post-war Berlin, Germany and Europe in 1945. This can be seen in Potsdam.

And finally, there’s a table in the Berlin district of Karlshorst. This one is on show in the venue where the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany was signed by Marshall Keitel on 8th of May 1945.

But it’s not the table in Karlshorst we’re are interested in here. It’s the sculpture in the garden of what is now the German Russian Museum.

It is has featured in the garden since 2005, and is called ‘Shot-through bridge stanchion Schlüterstraße’.

Catchy.

It’s a bronze work by a Dutch artist called Jan Henderikse, and is from 1998.

The actual cannon hole and stanchion depicted in Henderikse’s piece do really exist. They can be still seen today. They are a testament to the violence of the battle for Berlin here on the 28th April 1945.

Have a look here at my short video about this Berlin battle field damage for some details and location. Then, if you’re passing – you can check it out, or I can show you on this tour

There is only one slight problem with the sculpture. It’s name.

It’s not on Schlüterstraße. It’s on the train bridge crossing Leibnitzstraße, corner of Kantstraße, admittedly only a block west.

But still a near miss.

Berlin and its surroundings offer a fine line in historic tables.

We have the desk of polymath Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Goethe, that can be seen in the Märkisches Museum.

We have the table, around which the Truman, Churchill and Stalin sat deciding the future of post-war Berlin, Germany and Europe in 1945. This can be seen in Potsdam.

And finally, there’s a table in the Berlin district of Karlshorst. This one is on show in the venue where the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany was signed by Marshall Keitel on 8th of May 1945.

But it’s not the table in Karlshorst we’re are interested in here. It’s the sculpture in the garden of what is now the German Russian Museum.

It is has featured in the garden since 2005, and is called ‘Shot-through bridge stanchion Schlüterstraße’.

Catchy.

It’s a bronze work by a Dutch artist called Jan Henderikse, and is from 1998.

The actual cannon hole and stanchion depicted in Henderikse’s piece do really exist. They can be still seen today. They are a testament to the violence of the battle for Berlin here on the 28th April 1945.

Have a look here at my short video about this Berlin battle field damage for some details and location. Then, if you’re passing – you can check it out, or I can show you on this tour

There is only one slight problem with the sculpture. It’s name.

It’s not on Schlüterstraße. It’s on the train bridge crossing Leibnitzstraße, corner of Kantstraße, admittedly only a block west.

But still a near miss.

Anti-Semitism has a very long pedigree. Often, when one reads about gravestones being damaged in this context, it is Jewish headstones that have been targeted. This story is different.

The relationship with its Jewish community will forever be part of Berlin’s story. It is on the whole, a very ugly story, everywhere.

Today, Berlin’s monuments, exhibitions and study centres to this history are rather admirable. Here and there around the city are also reminders, tiny pin pricks of light in that deep, 12-year darkness as Hitler’s capital, that hint too at ‘what if?’ or ‘if only.’

The removal of reminders of uncomfortable history is an ongoing and contentious debate globally. Retrospective re-evaluations of the past often seem ignorant, lacking and lazy. The genuine relic, however uncomfortable the story it represents, cements authenticity and becomes a core around which discussion, fact and understanding can be built today.

Berlin has tussled with this debate, perhaps more intensely than other cities.

A Berlin metro station name came up for review recently. The station’s name – Möhrenstrs – or ‘Moor Street’ was the issue. No longer acceptable said some in today’s Berlin. This story has drifted from the front pages now, after a few new name proposals foundered. But if you missed the story here it is.

Berlin street names have been changed more often than most cities. Imperial period names morphed into Nazi. Then after World War II, both east and west Berlin relaunched with their own labels, and now there are some new modern ones too. It is a terrible irony that one of the longest lasting street names is Jüdenstrs, Jews Street, now both a testament and an accusation, and still signposted in the Berlin medieval period city centre area today.

One street name controversy that has rumbled for years, and seems pretty simple to resolve but hasn’t been, is Heinrich von Treitschke Straße. My daughter’s school was on this road.

He was an individual with unpleasant ideas, who lived in a time when many already knew better. Treitschke was quoted by the Nazi regime – if fact his quote appeared as a slogan on a newspaper front page every week, then available in all good Nazi newsagents near you – from 1923 until February 1945.

The name of the repulsive paper was the ‘Der Stürmer’, the content a slop of violent anti-Semitism and brutal adolescent pornography . The phrase was at the bottom of the front page was: ‘The Jews are our misfortune’

Violent antisemitism and brutal, emotionally adolescent violent pornographic fantasy sums up the Nietzschean ‘mass man’ that characterised many a the Nazi follower cum perpetrator. Godless, lawless, boorish, basic, childish, savage and completely unable to see their own degradation.

This should be born in mind when pondering today Hitler’s seemingly inexplicable appeal. The cheering masses in the beer halls, Hitler’s audience, where these folks.

Even the more erudite audience members experienced something peculiar. The German population, traumatised by the end of WWI and the myriad disasters of the 1920s, sought succour increasingly desperately, and in increasingly fringe places.

That is why Hitler was so effective. Millions of Germans abandoned the rational, the fair, and the logical and responded with a leap of faith to the emotional and self-interested, wallowing in dreams of revenge and the ecstatic vision of Hitler’s ‘quick fix’ redemption offer.

All you had to do was believe. Hitler’s speeches weren’t interesting, they were moving.

In this type of atmosphere emotive slogans and images wield power.

Hence the effectiveness of the phrase ‘the Jews are our misfortune’

Treitschke was a product of the main streams of German consciousness of the mid 1800s. As a member of parliament in the Reichstag he represented German nationalist parties and views. He was a contributor to a world into which Hitler was born. Treitschke is also quoted thus: ‘Brave peoples expand, inferior peoples perish’. This could easily have come from the Führer himself.

Where did these come from? Post French Revolution democratic fervour had spilled over into Germany by the mid 19thcentury. Industrialisation had produced a new, educated middle class that wanted representation. The workers and farmers too felt ripped off. The ruling aristocratic castes were afraid.

This catalysed debates about a new German democracy, nationalism, and imperial ambitions, often underpinned by crude notions of social Darwinism. Unfortunately, at this time, German Jewish emancipation was up for debate (again). There was also the sudden realisation that modern industrial economies and stock markets could fail. It was a new world in which some German Jews, brave and innovative, excelled. It’s failures demanded scapegoats.

These sentiments, combined eventually with broad feelings of national self-pity, jealousy (v. Treitschke was vocally anti British empire) and stupidity, contributed to the slide into World War I.

v. Treitschke died in 1896, not seeing that that he had in part inspired (the question of whether he would have been moved by Hitler’s speeches is moot as he was deaf).

He was buried in the St Matthews cemetery in Berlin, a resting place of more illustrious dead, perhaps these men are the most significant. Treitschke was a well-known figure, and his grave is substantial, made up of a costly, black-green granite head stone and flat grave-cover slab.

But today, if you look closely at this grave, you see now see something peculiar.

On the flat gravestone, under his name and dates, there are two carved scrolls. These remains untouched, and might have originally flanked a central symbol, perhaps an Iron Cross.

But at some point, probably in the 1980s, this part of the slab was ground down by persons unknown, mechanically, leaving the central section smooth and shiny. And then, with power tools, a neat star of David has been cut into the space. It’s deep and carefully executed. Only the left-hand angles seem a bit ‘off’. This hints that this person was perhaps not a professional, was determined (it’s cut into granite) and perhaps was working hurriedly as one would expect if one had lugged power tools, and a power source into a cemetery to amend a grave.

Who did this is remains a mystery. Why is pretty obvious. It looks like the ‘amendment’ will stay there as long as the grave. A strange victory.

The women who blew up Berlin.

Walk down any Berlin main street and you will be struck by its discordant architecture.

Today’s new 21st century glass and steel cages, still retaining the same mass as the rare surrounding surviving pre-war blocks, now fill the old vacant spaces left by WWII and the rare stone, bullet scarred facades of pre-1945 Berlin.

In between comes the bulk of ’50s and ’60s concrete boxes, the face of the Berlin’s great (and still ongoing) post-war relaunch. These were erected fast and cheaply, once the bombing rubble had been cleared away, to house tomorrows world. Symbolically, this fresh, modern style was chosen to represent a future in what was then the most important city in Europe.

These post-war buildings would become the faces of two choices of future, one in east Berlin and one in the west – a future under either communism or democracy.

Students of architecture would have sensed a continuity in this post-war city-wide style. It retained elements of the earlier architectural projects that fell under the broad label ‘Modernism’.

This early 20th century architecture was characterised by a shedding of historic styles, as a rapidly changing 19th century Germany industrialised, mechanised, urbanised and democratised. This new world demanded a New Berlin. Old Germany disintegrated, perishing as horse drawn Imperial carriages were replaced by electric mass public transport vehicles processing through Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate. This transition was so profound its fall-out dictated world history for the following century.

After WWII, the famed ‘Rubble Women’ cleared broken Berlin by hand, creating the ‘rubble mountains’ on both sides of the city. But one women was a different type of rubble women. She didn’t remove it. She created it. Her name was Hertha Bahr. And she blew up bits of Berlin.

There are very few images of Frau Bahr. She appears in broadcast of TV news in mid-July 1957. Berlin was still in ruins, and there amongst them is Hertha, surrounded by gangs of grinning men overalls. She is definately in charge. And she is laying charges as the footage cuts to here inserting dynamite into bore holes. Minutes later, the vast, ruined temple of industry, Lehrter Bahnhof (now Berlin Main Station), crashes to the ground.

Hertha Bahr was Germany’s first female demolition expert. Her company base was a renovated villa in the wealthy Grunewald district. Here she organised her operations. In the late 1940’s an eye witness account mentions her company involved in the demolition of buildings surrounding the famous Baroque Gendarmenmarkt Square in central Berlin.

All reports on Behr’s activities (admittedly a novelty), often seem obsessed with her appearance. This time it’s noted, she was sporting a ‘green silk blouse and red nail polish’. While she was at work here, folks were squatting in the rubble and cellars and refused to leave. One was nearly crushed by a falling wall.

Bahr’s first major commission was to destroy the building at the very heart of Hitler’s Berlin – the New Reich Chancellery from 1939. This project was a central part of the ‘denazifaction’ policy introduced by the victors in the late 1940s. Part of this ‘deprogramming’ was to remove Nazi period buildings to avoid them, in defeat, becoming places of sentimental memory of the Nazi regime. This was deemed necessary, its reported that tearful crowds gathered and sung outside the Chacellery in the immediate post war years. Even the wall plaster of Hitler’s mountain house was removed by locals as ‘the Führers breath had condensed in it’).

Though Hitler spent more time making key decisions and directing WWII from 2 other places than the Berlin Reich Chancellery (these were the ‘Wolfs Lair’ in Eastern Poland today and his ‘home’ – the Berghof – in Berchtesgaden – roughly 1000 days spent in each place) this building symbolised the core of his regime in the Nazi capital. Here was his office, and in the garden of the building his body would burn in 1945.

History does not record what she was wearing during this operation, (but it seems to have been a dark, roughish coat and black skirt).

In the late 1950s she destroyed Lehrter Station, and in the summer of 1960 the remains of Anhalter Station, leaving the entrance façade as a reminder of the ruins of war, perhaps a response to growing resistance amongst west Berliners that reminders of old west Berlin were practically all gone.

She was still working in west Berlin the 1970s, removing the ruins of domestic buildings for redevelopment, appearing in action depressing the plunger of a detonator in an article in the Carlisle Citizen newspaper based in Iowa. A white summer dress was apparently the choice here.

They quote her: ‘Blowing up a building is a safe as crossing the road, as long as you know what you are doing’.